A green awning outside the storefront announces Mott Haven’s newest outpost of Islam, the Masjid Ebun Abass on the quiet corner of Alexander Avenue and 141st Street, buffered from the traffic of Third Avenue by a Greenstreet triangle.

A symbol of the Bronx’s newest immigrant group, the mosque “is one of the biggest, and it’s in Mott Haven,” said Mamadou Kamara. Kamara is an assistant imam, the Muslim term for a spiritual leader.

Before the congregation leased its quarters, Kamara would travel to a mosque in Harlem to worship, and sometimes found himself praying in unlikely places. “When I do it on the street, I don’t care who cares,” said Kamara. “I once prayed in the Times Square Church.”

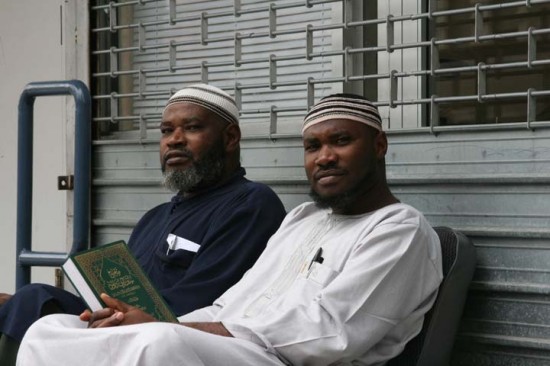

Most of the members of the congregation are West African. Their place of worship is a simple affair. A stepped podium for sermons, a bookshelf, and a poster of the Sacred Mosque in Mecca are the only physical signs of Islam in the mosque’s interior. Painted parallel lines on the carpet indicate the direction of Islam’s holiest city.

Brothers Ali and Habib Trawaly, who are respectively its imam and president, founded Ebun Abass a year ago.

“It was a considerable effort to bring about the mosque,” said Ali Trawaly. At the time, the only other mosque in Mott Haven was at 369 E. 145th Street, an anonymous century-old townhouse, where the only outward sign of Islam is a heavily barred green and white metal fence.

Starting a new congregation “was all about the kids,” said assistant imam Abdurahman Juwara. “They did not fit into the other masjid,” he said, using the Arabic term for mosque.

“We have over 160 kids here,” said Banusi Maha, 45, another of the founding members of the mosque. “We teach them to respect people.”

If it weren’t for the mosque, Maha fears, the children would instead be watching television and learning nothing. Instead, behind a makeshift curtain, children work on their school assignments and study the Quran.

Maha works an early morning shift as a cook at the Jekyll and Hyde Club, a theme restaurant in Midtown. Having worked as a chef in his homeland, he simply walked into the restaurant and asked for the job.

Like Maha, most members of the congregation hold blue-collar jobs, working long hours for little pay.

“Financially, it is difficult,” said Juwara, who emigrated from Gambia and has lived in the Bronx for 15 years. “We have a basement, but we don’t have the money to develop it,” said Kamara.

In contrast to the imposing, domed Islamic Cultural Center on the Upper East Side, which was largely financed by Kuwait, Masjid Ebun Abass did not receive funding from any foreign government. “If we had that kind of money, we’d buy the building,” Juwara said.

“This is us: we work in car washes, factories, and drive taxis,” said Degumeh Sillah, 60, an African art dealer. A Bronx resident since 1972, Sillah expressed pride at the religious transformation of the area. “The mosque on 166th Street,” he said, “that’s a former nightclub.”

Still, his mosque struggles to pay its $5,500 monthly rent. “With electricity, water, and teacher’s salary, that comes to $8,000,” said Sillah.

But the leaders of the congregation remain confident and determined.

“We are looking for a place to buy,” says Omar Trawaly, a cousin of the imam whose three sons attend classes at the mosque. He said that the landlord has given the mosque two months to consider buying the space. “For sure, we don’t want to be renting,” Trawaly said.

Local Africans often speak of making money and returning to their homelands, but months turn to years. Where it was once acceptable to pray anywhere, there is now a growing need for permanent institutions, including mosques.

“Before, we didn’t think of establishing masjids,” said Soulemane Konate, secretary general of the Council of African Imams. “It’s not easy for Africans to survive in this country, but we’re not leaving.”

A version of this article appeared in the Fall 2009 issue of the Mott Haven Herald.