On a recent Saturday, a young family of five shuffled along East 138th Street. Jimmy (who asked that the family name not be published) rolled a green duffle bag filled with clothes. With his free hand he held his 3-year old daughter’s hand.

His wife Cynthia pushed the baby stroller where her two-week-old daughter slept and carried her 2-year old daughter in her free arm. The family boarded a Bx17 bus to Fordham Road, where they left their luggage at Cynthia’s grandmother’s apartment, then returned to the Jackson Avenue Family Residence, a homeless shelter on East 138th Street and Cypress Avenue.

For a year and a half the family has bounced between staying with family members and living in shelters.

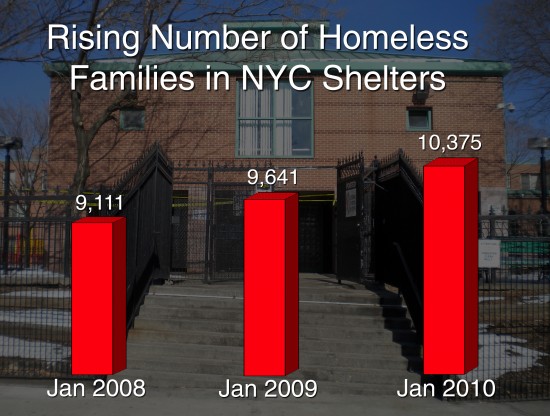

Jimmy, 30, Cynthia, 21, and their three little girls are among the approximately 12,000 families that by August 2009 were relying on the New York City department of Homeless Services (DHS) .

In the first four months of the current fiscal year, the number of families with children entering shelters increased by 25 percent, compared with the same period the year before, according to the most recent Mayor’s Management Report.

While the City Hall says it’s doing the best it can to combat homelessness, critics of its policies say a meager affordable housing program and a bureaucratic shelter system aggravate the problem.

“Over the past year more New Yorkers experienced homelessness than at any time since the Great Depression of the 1930s,” according to a report issued in March by the Coalition for the Homeless, an advocacy organization.

The reason is “an unprecedented economic downturn, both here in New York and across the country,” said Kristy L. Buller, the Department of Homeless Service’s deputy press secretary, in an e-mail response to questions. Her agency, she insisted, “is successfully meeting the demand each and every day.”

The city doesn’t keep statistics by neighborhood, but the figures it does keep show that a disproportionate number of the homeless families in shelters come from the Bronx.

Jimmy and Cynthia are among those families. Because a year and a half after entering the system they still haven’t been assigned to a long-stay shelter or an apartment, every 10 days they have to go to the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing office at 346 Powers Avenue in the Bronx to apply for permanent housing.

Beforehand, they have to all pack all their belongings and trudge with them to Cynthia’s grandmother’s. Then, while the city reviews their application, they retrieve their things and take them to a temporary shelter. They have stayed in shelters in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens.

It shouldn’t take a year for a family to find permanent housing, said Patrick Markee, senior policy analyst at the Coalition for the Homeless. But the city makes a “huge numbers of mistakes,” he said.

But the central problem, Markee argues, is that New York City doesn’t have enough affordable housing.

The coalition is pushing for more public housing to be built, and for reinstituting a federal housing subsidy that was eliminated in December 2009. But these long-term solutions can’t help Cynthia and Jimmy. They face more immediate problems.

Jimmy thinks it would be easier to win an apartment if he had a job, but he is illiterate, and says, “It’s hard to find a job when you can’t read.” He also suffers from depression, ans says, “I’ve tried to kill myself seven times.”

In the time Jimmy’s family has bounced from place to place, they have filled out more than half a dozen applications for permanent housing and have been rejected.

The application process can be complicated and intimidating. “Some of the paperwork can be confusing,” said Sarah Murphy, assistant of the executive director at he Coalition for the Homeless.

On a recent Monday, Cynthia and Jimmy received a letter telling them to be at the temporary housing office at 3 p.m. They left the Jackson Avenue Family Residence at 1:45 p.m. with their three girls, and walked a couple of blocks to the office.

Cynthia kept her eyes fixed on the ground and barely spoke. “We are bracing for the worst,” she said.

And that Monday, they were rejected for an apartment again, because, according to Cynthia, applicants for housing are required to present paperwork to show the their housing history for the past two years, and she and Jimmy couldn’t.

“It’s hard,” she repeated again and again. “It’s hard.”

They walked back to the shelter in complete silence. Jimmy’s looked exhausted. He hadn’t slept the night before and he had dark circle under the eyes. Cynthia was in tears, and the girls were crying, too.

Cynthia called a cousin in Pennsylvania to borrow money and ask for advice. After hanging up, she entered the shelter with her family.

A couple of weeks later, Jimmy had news. “We are in Pennsylvania,” he said. “We weren’t receiving help in New York.” He had found a job at Wal-Mart and was look