An exhibit detailing the history of “redlining” was launched at the Bronx Neighborhood Health Action Center in East Tremont in late January, to remind New Yorkers of what can happen when government doesn’t do its part to ensure that landlords are held in check from discriminating against minority tenants.

More than 50 attended the opening of “Undesign the Redline: Exploring the Transformation of Place, Race & Class in America.” The exhibit will be on display at the Bronx Neighborhood Health Action Center through March 30.

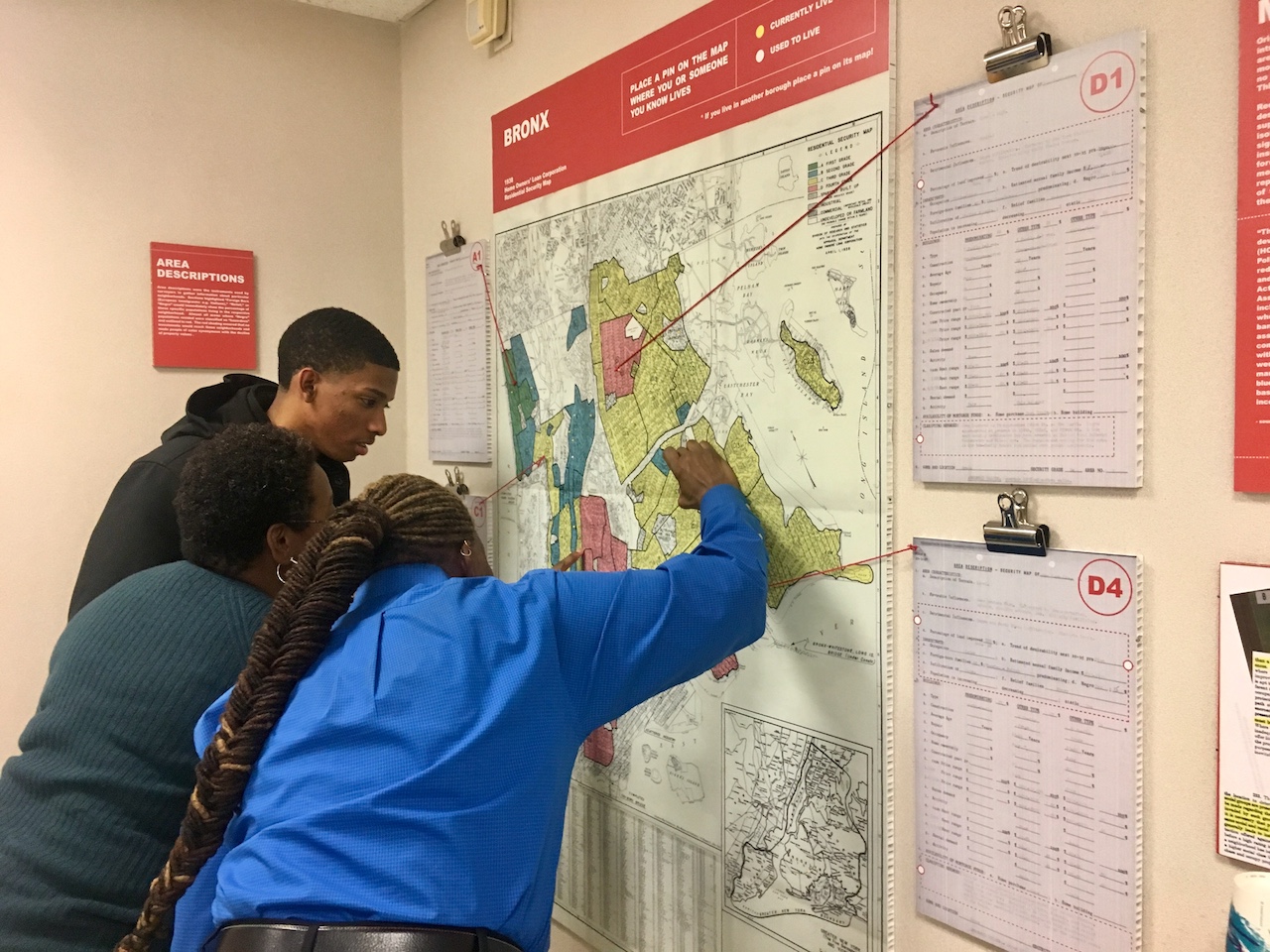

“Undesign the Redline” takes visitors on an interactive visit into a dark chapter in the nation’s past, as it details how racism permeated health care and housing, both in New York City and nationally.

“We don’t ask ourselves why, ‘why does it work like this?’” said Dr. Mary T. Bassett, commissioner at the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, who’s been dedicated to equal health care for all since she took the position.

On the first floor of the Tremont Center, the exhibit deep dives into the way the practice of redlining got started around the country. In the 1930s, the practice of outlining “hazardous” neighborhoods around New York City with a red pen was established to insure mortgages. That resulted in the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation.

In the pre-credit score era, the real estate industry’s assessment took factors like “detrimental influences: negro infiltration” into account. Over time these red areas were also less likely to receive municipal services, such as health care facilities.

The 1936 Federal Underwriting Manual of the National Housing Act states that “If a neighborhood is to retain stability it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes. A change in social or racial occupancy generally leads to instability and a reduction in [home] values.”

Residents are still paying the price today.

“How economical issues affect health has always been important to me,” said Bronx native Jason Carabalio, who attended the opening reception.

The lower levels of the exhibit offer interactive elements and even more eye-opening historical facts that have contributed to today’s current socioeconomic climate, dating back to the country’s founding days.

“Housing affects health,” said Rená Brown, a social worker who works with youth in the community. “There’s a real learning curve here.”