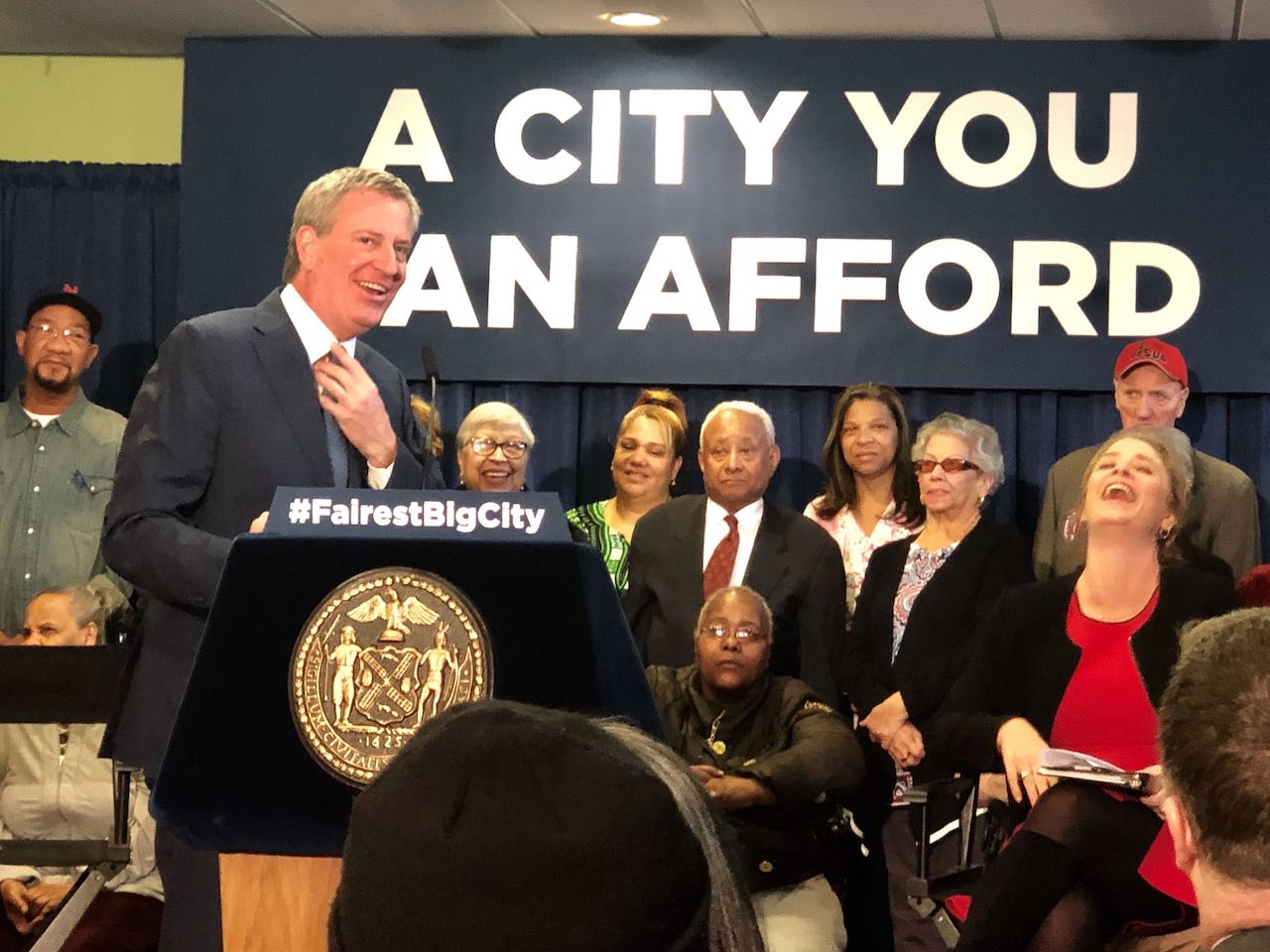

Mayor Bill de Blasio came to Melrose on Wednesday to tout what he said was a record breaking year for the creation of affordable housing in the city.

At a press conference at Borinquen Court, a complex built last year on 138th Street with 145 fixed-income apartments for elderly and/or physically handicapped people, de Blasio boasted that last year his administration was responsible for the addition of 34,000 apartments that the city says are affordably priced.

“Number one expense in our lives is housing. If we want a city for everyone, you want to city that looks like the New York we’ve always known and love, we have to do this,” said the mayor, adding that the city is back on track this year towards its goal of creating 300,000 affordable housing units within 12 years, after falling off that pace in 2017.

Although the mayor did not say why he chose Mott Haven as the place to sum up his administration’s achievements, he alluded to it by touching on the growing concerns over gentrification.

“We want to make sure people get to be in the neighborhoods that they protected, that they strengthened, that they saw through the tough times,” he said. “We have to make sure people are not displaced.”

But Ana Melendez, a case worker at Melrose housing advocacy group Nos Quedamos, cautioned that the city’s way of saying it is creating affordable housing, and looking after its low-income residents, can be deceptive.

“They assume that everyone who’s low income can move into these developments,” said Melendez. “But they’re not actually meeting the needs of an extremely low-income population.”

Two other buildings built in Melrose last year, 556 and 600 Bergen Avenue, have 495 apartments between them, of which the city classifies 220 as “permanently affordable.” Those units are available via lottery for applicants whose incomes range from $20,040 to $80,160 for individuals and $30,930 to $123,720 for a household of five.

For Melendez, those income requirements present a problem. Many of the affordable housing units popping up in the area and elsewhere in the city carry income requirements of $22,000 or higher, leaving out a large percentage of Bronxites who live on fixed incomes and government subsidies, she said.

There are other reasons the city’s current housing plan is flawed, Melendez added. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) has been distributing more vouchers to residents, to try to confront the record need for apartments. Theoretically that allows lower-income renters to land, and pay for, market-rate apartments. But instead of finding landlords who accept the subsidies, she said, the housing department often places voucher-holding apartment seekers in lower-priced apartments, leaving less room for residents who don’t qualify for vouchers or are still on the waiting list.

To complicate matters further, there are plenty of apartments that remain vacant in the area’s numerous New York City Housing Authority complexes, despite the Authority’s long waiting list. Melendez thinks the mayor’s focus on public-private partnerships is a way of avoiding internal issues in city agencies.

“NYCHA is like the rebel child of housing. There’s always something that NYCHA has to do that they’re not doing. So now compared to NYCHA, HPD looks like the hero,” she said. “But they’re all city agencies. They’re under the mayor’s arm. Why aren’t they looking at the fact that NYCHA’s not doing their job?”