Destiny, 17, has lived in homeless housing on and off since she was 13.

In September, she started her senior year of high school with 15 absences in the first month. By October, her grades had slipped below C’s and the administration had issued a warning. If she stayed on this track, she would not graduate.

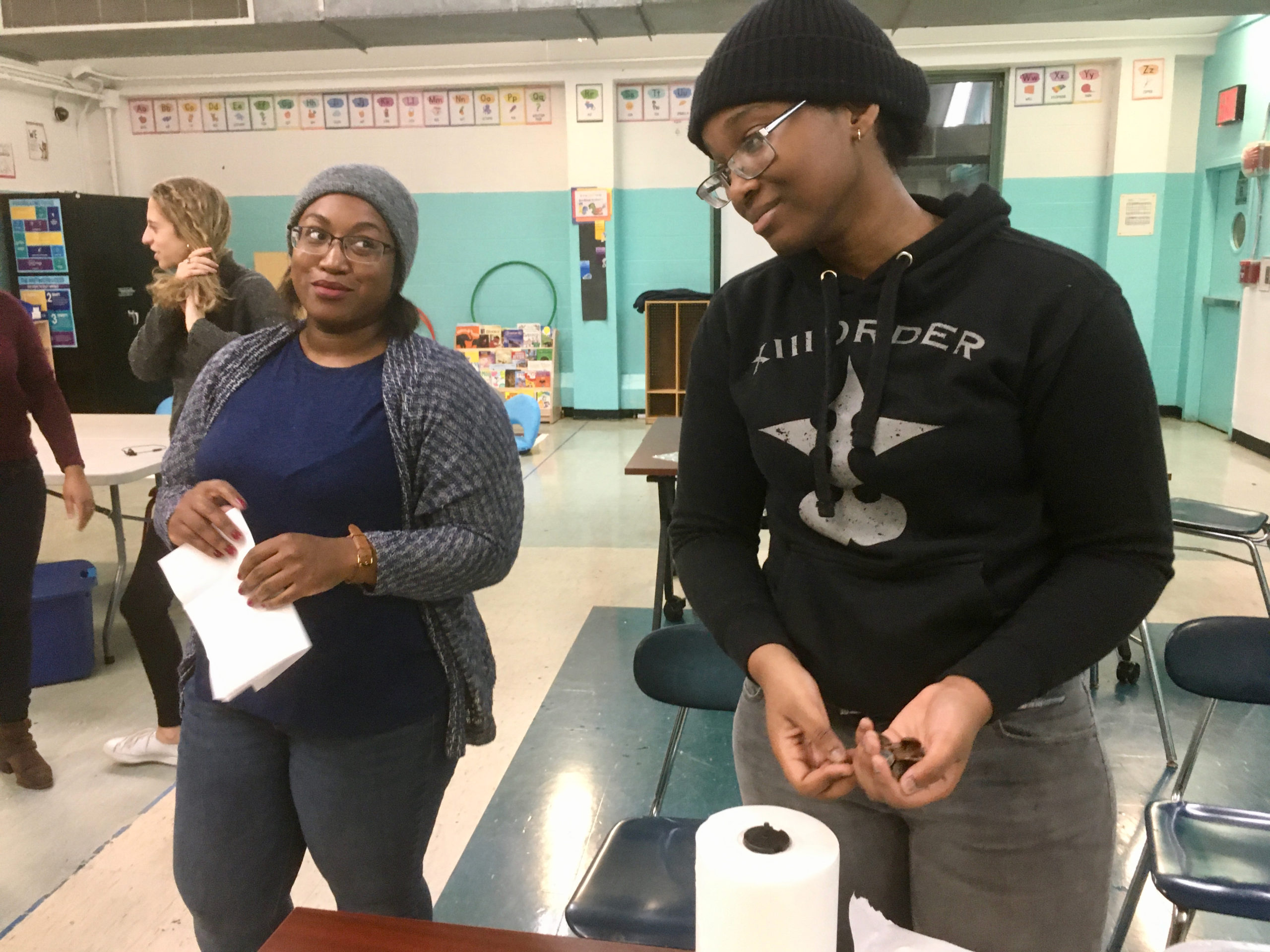

Six weeks later, Destiny sat at a table of four friends, leading their team, The Silent But Deadlies, through a post-lesson quiz on marine engineering. When the opposing team tossed paper across the aisle, Destiny refused to be deflected.

“Shhh!” Destiny hissed. “I’m over here trying to be smart!”

Since Oct. 21, Destiny and a group of 10 other high schoolers who live at the Powers Women In Need Inc. (WIN) shelter in Mott Haven have volunteered their Tuesday evenings to study engineering in the shelter’s recreation room.

Lessons are interactive. This week, students shaped aluminum foil into boats, filled them with pennies, then set sail on a water-filled Tupperware container to study buoyancy.

Funded by a $25,000 grant from AT&T Inc., the program aims to expose a more diverse population of students to future careers in science, technology, engineering, arts and math (STEAM).

But the program’s small group structure has had a more immediate impact, working to curb the abysmal educational outcomes that non-profit Advocates for Children of New York found about students living in shelters.

Lawrence, 17, and his mother, Stacy, 48, moved into Powers over a year ago. Stacy said Lawrence had always been a strong student, while a shy one.

When he started the Powers program, Lawrence said he didn’t know any of the other students, kids he’d lived with for over a year. But, after four weeks, he’d made a tight group of 10 friends, plus a subway buddy for school.

In a section of the Bronx where Advocates for Children found that nearly 20% of students are homeless and only 45% of students in shelters graduate high school, having friends committed to learning can increase a student’s propensity for success.

“Giving youth activities that engage them, and peers and adults who challenge them and can serve as role models for them, helps students engage in school,” said Randi Levine, policy director at Advocates For Children.

For many homeless students, the larger obstacle to graduation is their commute.

When students enter the shelter system, they’re often forced to move out of their school district, and for nearly half of New York City homeless students the move is to another borough.

Destiny said her hour and 20-minute ride often meant a missed alarm was a missed day of school.

“I’m not an early bird,” said Destiny. “So, if I get up late, it’s like why bother.”

While programs like Powers’ can’t shorten that distance, they can curate the type of community that motivates a student to brave the commute.

“Particularly for the teens that we’ve engaged, I firmly believe that having these additional supports in the shelter does promote attendance and does promote a sense of community and self-esteem,” said Sasha Njoku, director of Youth and Enrichment Services at WIN.