With new funding, youth programs in the Bronx are expanding to serve those at risk for violence in their communities.

Bronx Rises Against Gun Violence (B.R.A.G.) announced that private foundation grants as well as federal, state, and city funding will allow them to double in size and open three new programs, though it has not yet identified where they will be located or when they will open.

B.R.A.G., which operates through Good Shepherd Services, works with young people ages 16 to 25 through programs in the borough’s Wakefield, Belmont, and Fordham sections. Launched in 2014, its founder, David Caba, says it’s more effective than law enforcement at preventing violent crimes like shootings. This is because they employ “credible messengers,” former at-risk youths who have returned to their communities to work for the group.

“We have a reach that our credible messengers have that the regular law enforcement official doesn’t have, the regular politician doesn’t have, the regular social work, or mental health expert. We have a reach they don’t have.”

New York City, like other cities across the US, is experiencing rising crime rates. The city is opposing reductions to police budgets but would also like to see financial contributions to community resources like youth programs. The Department of Youth and Community Development, which funds after-school programs and other youth services, lost 32% of its budget in 2021, but the city is allocating an additional $42.6 million for its 2022 funds.

Though, overall, crime in NYC has declined in the last year, homicides and shootings are going up in the Bronx. Caba attributes this to the pandemic and the way it exacerbated issues that have long existed in the Bronx, like lack of access to healthcare and mental health resources, inadequate housing, and unemployment.

He says the answer is to refund the community with organizations like his rather than beef up the police budget.

“If you take a look every time you provide a resource to community, like, we’re it. At B.R.A.G., you have provided us with tons of funding and look at what we have produced.”

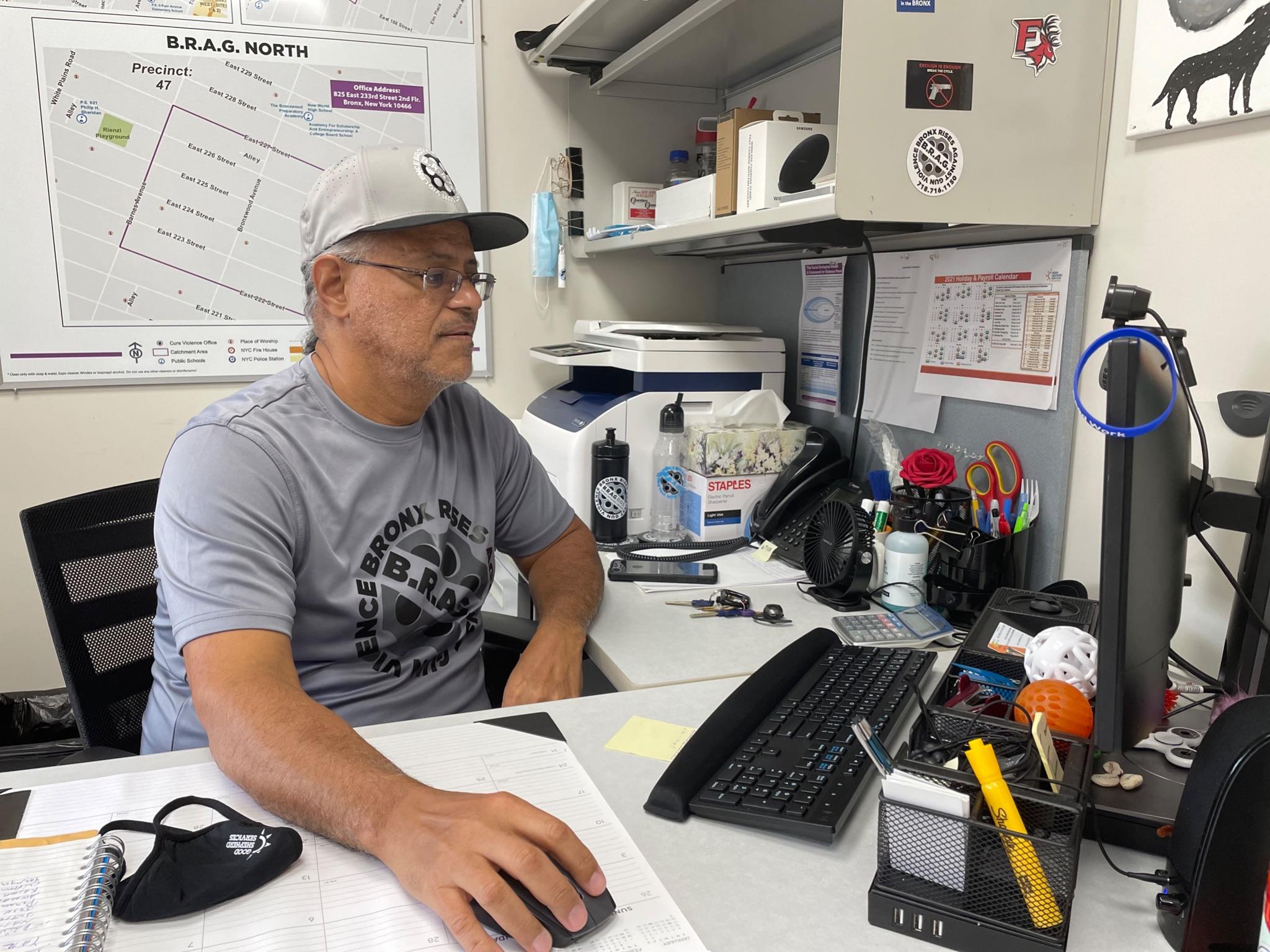

Caba, whose office walls are covered with maps of the neighborhoods his program targets, says the proof is in the results. Since the Wakefield opening in 2015, 660 days passed without a shooting, according to Caba. He says their Northwest program experienced a 50% reduction in gun violence.

Caba attributes the successes of B.R.A.G.’s initiatives to its “credible messengers,” employees who are from the neighborhoods where they work and were once considered high-risk for violence themselves.

Keith Black, 46, is a credible messenger at the Wakefield office, where he has been working with the program for five years, and is part of the violence interruption team.

“You know credible messengers, the term really means, you know, we was in that position at one time. We went outside and we came out, we saved our lives, and now we want to, you know, fix the community that we once was breaking.”

A large part of B.R.A.G.’s initiatives involves going into schools to talk with local kids. Caba says this usually starts with middle school, but he’d like to start working with even younger kids, “We really should be in the elementary schools because that’s where the prevention lies, right?”

Another nonprofit, One Village One Voice, just north of Olinville is working with children as young as eight years old, the age Caba says he was when he started carrying a gun, providing them with after-school programs. They too are expanding and will start providing services at a second church in the area.

Its founder Keven Finlay, 47, grew up near Wakefield. His program offers afterschool and weekend sports activities, like boxing and basketball, and mentoring services to “just show the kids a different way of life and how to go about living and how they grow into adults,” says Finlay.

He says youth programs are “not available, too costly, or out of reach from our neighborhood,” which is what motivated him to start his own.

Their Facebook page includes images from his Saturday boxing classes with young kids posing in their boxing gloves.

Youth programs are just one way to refund communities, says Caba. He also mentions the importance of education, housing, and healthcare.

Lacking basic needs, he says, is what creates trauma and pushes kids closer to guns in the first place:

“Of course, you’re going to gravitate to safety, you know? And what does that mean? That means you have to carry something to keep yourself safe, to protect yourself from others.”

If kids don’t have their needs met, he says, “The street is always waiting, is always calling.”