Aurely Negrón’s studio apartment in the Mitchel Houses in Mott Haven has had mold since he moved in 10 years ago. Earlier this year, a leak in the apartment above flooded his bathroom, causing the medicine cabinet to fall out and expose old plumbing, which a laboratory found to contain asbestos. The problems have yet to be repaired.

“I’m very disappointed with NYCHA,” says Negron. “They have a code of standards, but they don’t follow that.”

Public housing comprises the majority of housing that is affordable to extremely low-income families in New York city. But throughout New York City, projects have fallen into disrepair due to decades of public disinvestment. NYCHA estimates it needs $40 billion for repairs to its more than 170,000 apartments — a figure that grows by $1 billion every year.

New funding from Washington could be a game-changer. On Nov. 19, the House of Representatives passed its version of the Build Back Better Act, containing $65 billion for public housing investments across the country. A considerable chunk of that could be destined for NYCHA, America’s largest public housing authority, which accounts for around 18% of public housing in the country.

NYCHA officials have said they would use the funds for comprehensive modernization projects, from roofs to plumbing to heating systems.

However, a lot is still uncertain. The Senate could reduce or eliminate public housing funding when it votes on the bill — Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has said he wants a vote before Christmas.

And even if the $65 billion survives, it is unclear what effect NYCHA’s share could have on its long-standing plans to address budget shortfalls through the Rental Assistance Demonstration program and the proposed Blueprint for Change, both of which involve greater collaboration with the private sector.

“There are a lot of unknowns right now but we have been creating infrastructure and management systems that are prepared to receive capital…and spend it effectively,” Rochel Leah Goldblatt, NYCHA’s deputy press secretary, told the Herald.

In the Mitchel Houses, where Negrón lives, mold and lack of heating are common problems. The elevators frequently break down, so wheelchair-bound residents sometimes have to be carried down the stairs to enter and exit. In November, a six-year-old boy died in a fire that started in a trash compactor.

Many of these problems, which echo those reported throughout NYCHA complexes, are due to a lack of funding. Government budgets for capital repairs decreased 35% between 2020 and 2021, according to Human Rights Watch.

NYCHA’s $40 billion repair estimate for all its buildings is based on a 2017 physical needs assessment, plus inflation, plus costs associated with meeting an agreement signed with HUD in 2019 as part of a lead-paint lawsuit.

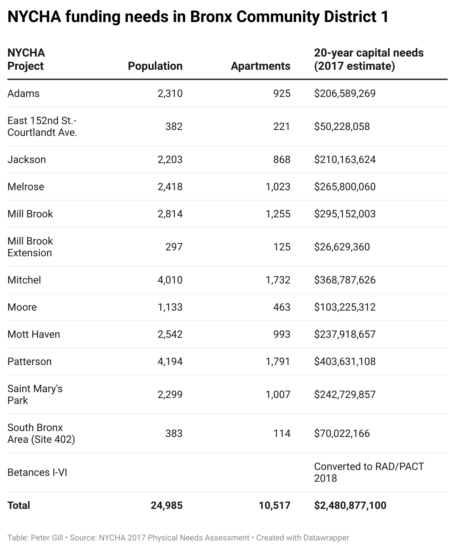

In Mott Haven, Port Morris and Melrose, nearly 25,000 people live in 12 NYCHA-managed projects. The 2017 assessment put these buildings’ needs at $2.48 billion over the next 20 years.

While funds from the Build Back Better Act could help cover these costs, it may not be enough to alter NYCHA’s ongoing strategy of raising capital through public-private collaborations.

Under the Rental Assistance Demonstration program, created by the Obama administration, NYCHA began a process of transferring 62,000 apartments to private management companies in 2015. Residents are given Section 8 housing vouchers to pay rent to the management companies, which are then responsible for undertaking repairs.

While NYCHA says that conversion to Section 8 has improved conditions in buildings transferred to private ownership under RAD, many residents disagree.

Daniel Barber, president of the Jackson Houses Resident Association and chairman of the Citywide Council of Presidents, said repairs made under the program are often cosmetic, and fail to address underlying issues.

“It’s just a bandaid,” Barber told the Herald. “RAD and PACT are taking the ‘public’ out of public housing.”

Activists and rights groups say that the housing conversions disenfranchise residents. Conversions have led to a loss of protections for residents and can increase evictions, Human Rights Watch said in a recent letter to Congress.

Nonetheless, the conversions continue. In Bronx Community District 1, the Betances Houses were converted to Section 8 in 2018, under Wavecrest Management. At least two other projects in the area— Moore Houses and South Bronx Area (Site 402) — are slated for conversion.

NYCHA CEO Gregory Russ has also proposed a plan, the Blueprint for Change, for the city’s other 110,000 units that will not undergo Rental Assistance Demonstration conversion. The Blueprint proposes to hand over management of these units to a public trust, which would use a combination of public and private investments to make repairs.

NYCHA would apply to the federal government for tenant protection vouchers, a special type of Section 8 housing voucher for apartments in extreme disrepair. The housing authority would then issue bonds to raise private money for repairs and use the protection vouchers to pay off the bond debts.

Russ first proposed the Blueprint in July 2020, but state lawmakers in Albany need to approve creation of the trust before the plan can move forward. NYCHA says the Blueprint is an antidote to years of disinvestment by the federal government. It claims that the Blueprint would not affect tenants’ rights, and it has received support from some policy experts and others.

However, many residents oppose it.

Ramona Ferreyra, a neighbor of Negrón at Mitchel Houses, thinks that the Blueprint’s tenant protection vouchers create a perverse incentive by rewarding NYCHA for neglect. She is participating in a rent strike to demand better living conditions and is a founding member of Save Section 9, an organizing group that holds teach-ins about the Blueprint for NYCHA tenants.

During a Nov. 18 City Council hearing on NYCHA, tenant organizer Marquis Jenkins questioned whether the rationale for the Blueprint for Change would disappear if federal funding comes through.

In response, NYCHA Vice President Brian Honan noted that the Build Back Better Act, if passed, will provide funding for NYCHA’s capital expenses, but not operating costs.

“We will still have an operating issue that we will have to deal with. Once we have a final dollar amount, that will determine the next course on the trust,” he said.

Barber is optimistic about new federal funding, even though the $65 billion in the current version of the Build Back Better bill is less than the $80 billion he originally hoped for.

“I haven’t given up. We didn’t think that we’d even get this far,” he told the Herald.

Ferreyra is less hopeful. The bill contains $1 billion for tenant protection vouchers, which could be used to move programs like the Blueprint forward.

“Putting additional capital funding in NYCHA’s hands doesn’t guarantee that there’s going to be a difference in the quality of life of tenants like me,” she said.