Environmental justice advocates say a massive federal plan to protect New York City from coastal flooding puts the South Bronx in the back seat, and fails to address existing environmental inequalities.

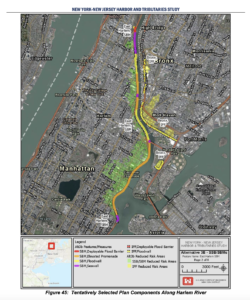

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is in the final days of collecting comments for its $52 billion New York & New Jersey Harbor and Tributaries Focus Area Feasibility Study, which proposes a variety of measures, including building seawalls and elevated promenades, to prevent coastal flooding similar to what the region experienced during Superstorm Sandy in 2012.

The study, authorized by Congress, is in its initial stages and any finalized proposal likely won’t be built until at least 2044. Still, it has the potential to radically change the shape of New York City’s coastlines and has raised concerns about furthering existing environmental injustices.

In the South Bronx, the Army Corps’ “tentatively selected” draft plan proposes building flood walls and deployable gates stretching roughly from Yankee Stadium to the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge at the base of Randall’s Island, while the Hunts Point peninsula is left entirely unaccounted for.

Port Morris: flood protection without community control

The flood wall proposal along the Port Morris waterfront is considered by the Army Corps as an “induced” measure. That’s because on the Manhattan side of the Harlem River, building flood walls and an elevated promenade would actually increase the risk of flooding in The Bronx.

While much of the South Bronx is at a relatively low risk of flooding currently, preventing water from streaming into East Harlem means that water still has to flow somewhere else – in this case, into Port Morris.

The flood walls proposed in Port Morris were “not created to get rid of all risk,” said Victoria Sanders, a research analyst at the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance. “It’s to minimize the risk that they’re actively causing. So not only are they not properly protecting the South Bronx, they’re actually kind of using it as a sacrifice.”

“They have kind of, at least at this point, written off the South Bronx,” she added. “It’s not looking at social vulnerability and environmental justice and what do those communities need and deserve.”

In its determination of which type of infrastructure to build where, the Army Corps is basing their plans off of existing conditions, explained Danielle Tommaso, an Army Corps planner. If a neighborhood previously had a waterfront park, the plans would preserve it by rebuilding a waterfront promenade. In neighborhoods like Port Morris meanwhile, that don’t currently have waterfront access, the plan proposes concrete walls that would further cut communities off from the water.

That’s concerning to Arif Ullah, executive director of the nonprofit South Bronx Unite, who thinks waterfront access should be prioritized in Mott Haven.

“To say that only existing features would be the determinant for deciding what goes there is perpetuating injustices because our community does not have open green space, for the reasons of racist public policies and racist planning decisions,” he said in an interview with the Mott Haven Herald.

“It’s not that the Army Corps is ill-intentioned,” Ullah said, but “the study did not include thorough analysis of each of the communities through which sea walls and other infrastructure would be built.”

South Bronx Unite has, since 2015, been developing a community-directed plan for the Mott Haven and Port Morris waterfront, that would be controlled by a community land trust. Much of the land along the waterfront is currently owned by the State Department of Transportation and subleased to companies including FreshDirect.

The Army Corps, Ullah said, has expressed a willingness to work with South Bronx Unite and other community organizations, and it remains to be seen what a final proposal will look like.

“This is just a first stab at a concept, this is probably not what is going to ultimately be built,” stressed Tommaso, the Army Corps planner, during a public meeting at Cardinal Hayes High School earlier in March. “So considerable work remains to be done before we have the detail to know exactly what we’re doing in your backyard.”

Are storm surges the greatest risk facing the South Bronx?

Overall, Sanders said she is concerned that the Army Corps is focused solely on protection from storm surges, without taking into greater account other risks posed by heavy rainfall events like Hurricane Ida, or sea level rise.

“They’re so focused on storm surge, that they’re going to miss the mark and not actually protect the region from all of the threats that it faces in terms of coastal resilience,” she said.

She said she’d also like to see less “gray infrastructure,” meaning physical, concrete barriers, in favor of “nature-based solutions,” like marshes and wetlands, whenever possible.

Any final measures in Port Morris might be affected by whether other projects move forward. Last week, Mayor Eric Adams announced plans for a seven-mile greenway along the Harlem River, stretching from Highbridge to Mott Haven, made possible by a $7.25 million federal grant.

A representative from the Department of Transportation said that while the greenway was in its initial stages, it would work with the Army Corps and FEMA “as necessary.” A series of public workshops on the plan begin on April 18.

The Hunts Point Peninsula remains overlooked

The Army Corps’ plan ends to the east of the Robert F. Kennedy bridge, leaving Port Morris and the Hunts Point Peninsula unprotected.

“Unfortunately it’s not surprising,” said Dariella Rodriguez, a longtime community organizer at The Point CDC in Hunts Point.

“It’s scary that Hunts Point, the place where the tri-state area’s food distribution center is, is not being protected,” she said. Since Hurricane Sandy, the low-lying Hunts Point Food Market has invested in hardening its electrical grid, but it still remains at risk of flooding.

Hunts Point was largely spared from the worst effects of Sandy thanks to a low tide, but Rodriguez worries it might not be lucky next time.

“That’s something that we will be looking at in terms of the study,” Carisa Norman, a project management specialist with the Army Corps, said at the South Bronx public meeting, referring to Hunts Point. “It is important … not just to the city but to the whole region.”

Last month a coalition of community groups, including the Bronx River Alliance, released a statement with objections to portions of the Army Corps plan, noting that while it protects some urban waterways it leaves “others—many of which lie in environmental justice communities—entirely without protection, effectively turning them into sacrifice zones in the event of a major storm.”

“They have this cost benefit analysis that they use, and in our view, it’s really biased and out of date because it’s only really thinking about property values and traditional ways of looking at risk,” said Sanders from the Environmental Justice Alliance, which also submitted comments in partnership with the Columbia Climate School’s Center for Sustainable Urban Development.

The comments note that “many excluded areas of the [Army Corps] plan include industrial waterfront land use areas” that are “crucial to the social fabric of frontline communities and must use harmful chemicals in their normal operations,” potentially compounding the risks posed by flooding.

The Army Corps isn’t “looking at social vulnerability and environmental justice and what do those communities need and deserve,” she said.

The deadline to submit comments on the Army Corps of Engineer’s tentatively selected plan is March 31. Comments can be submitted to the following email: nynjharbor.tribstudy@usace.army.mil