Most middle schoolers worry about making new friends and remembering their locker combination.

But New York City’s eighth graders are faced with another challenge: getting into a competitive high school.

The complex high school application process opened on Oct. 3 and closes on Dec. 1, giving eighth graders a narrow window to choose up to 12 schools they want to apply to, out of more than 400.

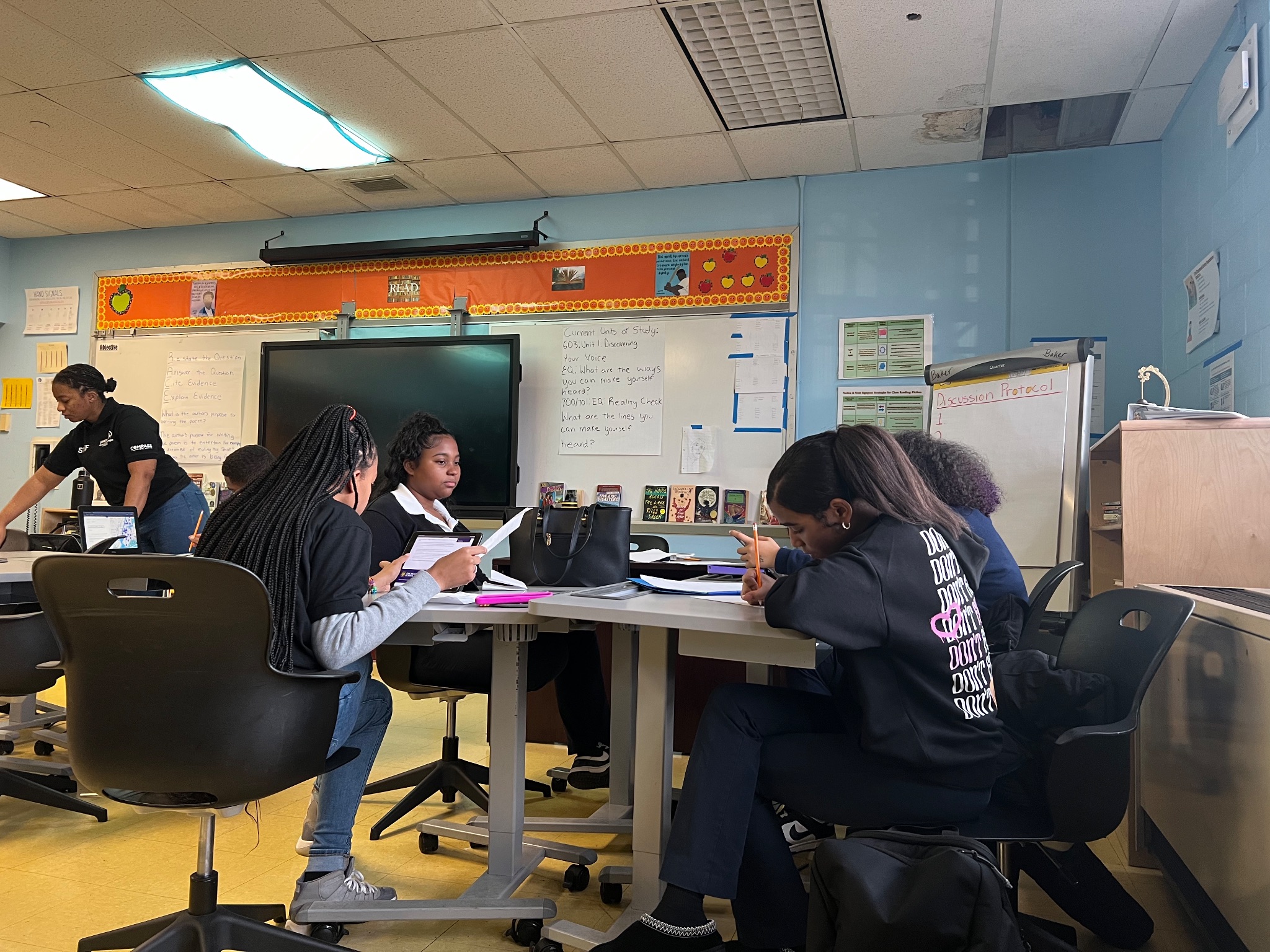

Since 1999, WHEDco, a nonprofit organization, has run an after-school program for over 450 students grades K-8 at PS/MS 218 in the South Bronx. They help eighth grade students pick their top high schools, workshop their application essays and keep parents and families informed on deadlines.

After-school programs like WHEDco’s are especially needed in neighborhoods like the South Bronx, where schools were hit hard by COVID-19. Last year’s state standardized exam showed that Black and Latino students, as well as those from low-income families, suffered more from remote learning.

WHEDco participant Jordan Vargas, 13, is happy to be back in the classroom after falling behind in math during remote learning.

“School during COVID was very hard,” said Vargas. “Sometimes the internet would be slow and I wouldn’t be able to join the classes.”

Vargas prefers in-person instruction because he gets to see his friends and receive direct help from his teachers. He also said in-person learning gets kids off their phones and keeps them focused.

Barriers like access to reliable technology can impede a smooth application process and test scheduling. About half of New Yorkers living at or below 150 percent of the federal poverty level do not have high-speed internet at home and over 600,000 people in lower-income households do not have broadband internet access, according to the American Immigration Council.

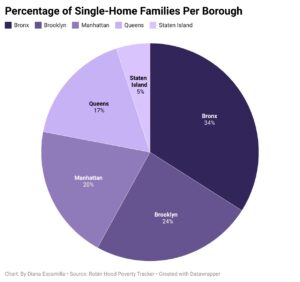

Additionally, working parents have less time to help their kids pick and apply to schools. Single-parents households, which are more common in the Bronx than any other borough, struggle more to ensure their children’s preparedness for school and to find after-school care.

“The resources aren’t the same,” said PS/MS 218 Assistant Principal Elvia Núñez.

Opportunity gaps for lower-income students and students of color are starkly apparent in the application process for New York City’s Specialized High Schools, which have a reputation for serving the city’s most ambitious students in academics and the arts.

Students must take the Specialized High Schools Admissions Test, or SHSAT, if they wish to attend one of the nine most prestigious high schools. The test is the only material used to determine admittance to these schools, a process that opponents of the test say disadvantages students who receive less training in test-taking.

This year, only 10 % of offers to Specialized High Schools went to Black students, while only 6.7% went to Latino students.

But these two groups make up over two thirds of the city’s student population. At PS/MS 218, 92% of the students identify as Hispanic or Latino.

“I’m not surprised by that,” said Cha-Dasia John, 23, a specialist at the WHEDco after-school program at PS/MS 218. “A lot of it comes from the fact that our parents don’t really know how to maneuver through the system and they don’t know as much information.”

Thus, a life-changing decision falls onto the shoulders of 12- and 13-year-olds.

PS/MS 218 student Destiny Torres, 13, sat for the Specialized High Schools Admissions Test for her application to LaGuardia High School. The performing arts high school also requires an audition for admittance, and Destiny hopes to study dance.

As a participant in WHEDco’s after-school program, she’s received one-on-one help with her application in class.

“I actually like going to that class,” she said. “It’s not even horrible. It’s not a bad class.”

Ultimately, her dream is to be a therapist because she wants to help others.

Núñez said she would like to see more of her students get into the Specialized High Schools. Part of reaching that goal is to foster their creativity outside of the classroom.

In addition to the high school prep program, WHEDco offers kids “home economics” activities, like baking and sewing, as well as programs in sports and the arts.

Fostering students’ artistic and athletic abilities not only builds confidence, but further helps them narrow their choices for high school based on the types of activities they want to pursue.

“I tell the students, ‘You have the skills in you,’” said Núñez. “Sometimes they don’t know that they have it, so being exposed to those extracurricular activities opens a door to the students to figure out, ‘What am I good at?’”.

Vargas found his answer to that question through his time at WHEDco, and now he’s eager to know which high school he will attend next year.

“It will be a big step towards my goal, because currently my goal is to play basketball in the NBA,” he said.

Vargas only started playing basketball in sixth grade, thanks to a WHEDco program. Now his top choice high school is Beacon High School because they have a reputable basketball program.

Students who are impoverished and of color benefit the most from the social, academic and emotional support accessed through a quality after-school program, according to a Boost Collaborative report.

But John says after-school programs aren’t enough on their own to give her students the same opportunities as students in wealthier school districts.

Increasing parent engagement, paired with the support of an after-school program, would breed greater success, she said.

What most inspires John about her students over the years is the bond they have. She sees them motivate each other to take the high school admissions process – and with that, their dreams – seriously.

“That pushes them to do what they need to do,” she said.