Bronx social justice organizations hosted a town hall on Dec. 5 to raise support for the proposed “How Many Stops Act,” to increase transparency around policing in New York City, especially the controversial practice of stop and frisk.

The event at the Bronx Defenders Office was hosted by the Communities United for Police Reform, a coalition of organizations including the Bronx Defenders and the Justice Committee, a grassroots group focused on ending police violence. Advocates of the legislation discussed the relevance of the bill to the Bronx, where they said stop and frisks have been on the rise.

The “How Many Stops Act” includes two bills – one would require the NYPD to record level 1 and 2 or “low-level” stops, where no “reasonable suspicion” of illegal activity exists; the second would require NYPD to report more data on searches that those who are stopped consent to.

This reporting would provide data surrounding language access, racial demographics, as well as creating a written record of all the stops and searches conducted by NYPD.

Currently, only level 3 stops, which require “reasonable suspicion” and detainment, must be reported. Level 1 and 2 stops can involve information requests, “accusatory” questioning, and requests for consent to search. If a person being questioned attempts to leave, a level 2 stop can advance to a level 3.

Historically, stop and frisks have been proven to disproportionately target Black and Latino individuals. In 2013, a federal judge ruled the NYPD’s stop and frisk practices unconstitutional in how they were being conducted, and required the department to create and follow clear guidelines for stops. The number of stops initially plummeted but since 2022 have been on the rise.

According to a report filed by federal monitor Mylan Denerstein earlier this year, 97% of stops by “Neighborhood Safety Teams,” NYPD anti-crime units appointed by Mayor Eric Adams, involved Black and Latino people. According to testimonies from panelists and audience members at the Bronx town hall, this experience is mirrored in the Bronx and New York City at large.

Advocates hope that increasing information and reporting around all kinds of stops will encourage accountability from NYPD so that these stops aren’t happening as recklessly and with racial bias.

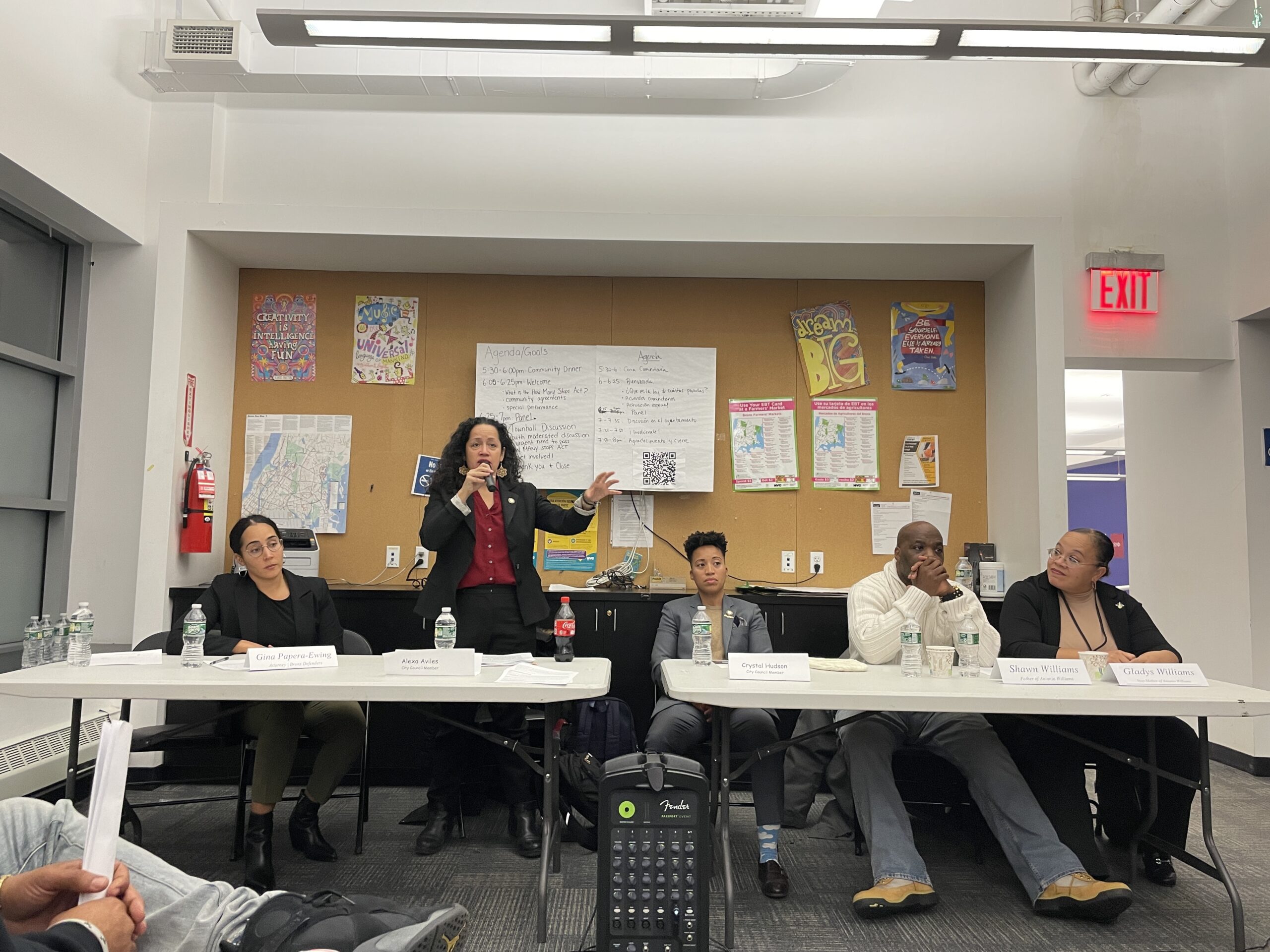

“That is not healthy, that is not public safety,” said Council Alexa Avilés from Brooklyn, who is the prime sponsor of one of the two bills. “You should not be thrown up against a wall because you are Black or Brown. That is not okay.”

According to Avilés, without the data that would be provided by the How Many Stops Acts, it is difficult to understand the full scope of the issue.

“Without the data, the PD and anybody else can just hide,” said Avilés.

If the legislation is not passed and signed before the end of 2023, council members will need to start from scratch – a reason for the push to find new sponsors or members who commit to vote for it. The legislation currently has 30 cosponsors and will need 34 votes to pass the Council. Three City Council members who represent the Bronx – Rafael Salamanca, Marjorie Velasquez, and Jeffrey Dinowitz – have not yet agreed to support the How Many Stops Act.

Council Member Althea Stevens, who represents a Bronx district, attended and voiced her support. Speakers encouraged attendees to urge their representatives to vote in favor of the bills.

Student advocate and former Bronx Defenders intern Makeda Byfield moderated a panel discussion among advocates, including council members and family members of New Yorkers killed by NYPD.

Shawn Williams, whose son Antonio was killed by police, told the crowd that if the How Many Stops Act had existed, his son might still be alive today. Antonio was killed during a low level stop in 2016 by a plainclothes anti-crime unit. Those units were disbanded in 2021 following the George Floyd killing but were brought back by Adams in 2022 as Neighborhood Safety Teams.

“Antonio was a son, a twin, a father,” said Williams. “Because of violent actions by the NYPD NST crime unit, Antonio’s kids will never grow up with a father.”

After the panel, audience members told stories of harrowing experiences with police stop and frisks.

“I don’t tell my mother anymore when I get stopped,” said Sammy Feliz, whose brother Allan was killed by police in the Bronx in 2019. He doesn’t want to compound her trauma after losing one son.