In the wake of torrential rains that have put much of the city on flood watch and disrupted travel in parts of the Bronx, the threat of flooding is increasingly affecting New Yorkers—and it may get worse due to climate change.

A warmer planet also means a wetter planet. A warming atmosphere will hold and dump more water, while warmer oceans create sea level rise and more intense storms and hurricanes. Heavy rain events are expected to increase by two to three times the historical average by the end of the century, according to a federal Climate Science Special Report released in 2017.

Bronx County has an extreme risk of flooding over the next 30 years, according to Risk Factor, a tool created by non-profit First Street Foundation to measure the projected effects of climate change across the country.

“When we’re getting these really heavy rainstorms, that water doesn’t go anywhere,” said Christian Murphy, ecology coordinator at the Bronx River Alliance. “When it used to enter our marshes and our wetlands and all these beautiful spaces that used to be in the region, now it just floods people’s homes, and it floods our subway stations, and it floods our highways.“

The dangers of floodwater aren’t limited to property damage—it poses health risks as well.

About 60% of the city’s sewer system is a combined sewer system, meaning stormwater and wastewater mix together in a single pipe and flow toward a wastewater treatment plant. But if the flow reaches twice the capacity of the treatment plant during heavy rain, excess water is directed into local waterways to prevent damage.

These waterways that are now contaminated with untreated wastewater can then overflow during storms and mix with floodwater, exposing people to the bacteria that come along with it.

“If it’s coming out of the toilet, it’s going to be in the river at some point,” said Murphy. “The sewer system was built as the city was growing. It’s old, and it doesn’t have the capacity to handle what we do to it in the modern day, and it has not kept up with climate change.”

Toxic chemicals and other hazardous substances can also be an issue when floodwaters pick up trash, fertilizer, or industrial waste from the ground. Once it goes down the drain, it could end up in the separate storm sewer system, which makes up the remaining 40% of the city’s sewers. Different pipes carry wastewater to a treatment plant while the contaminated stormwater is sent directly into local waterways.

This is especially relevant to the South Bronx, where the waterfront is one of seven Significant Maritime Industrial Areas, known as SMIAs. These zones were designated in 1992 to cluster heavily industrial and water-dependent infrastructure—and the pollution they create—into certain areas in New York City. The South Bronx SMIA is the largest, at over 850 acres, stretching across Port Morris and Hunts Point.

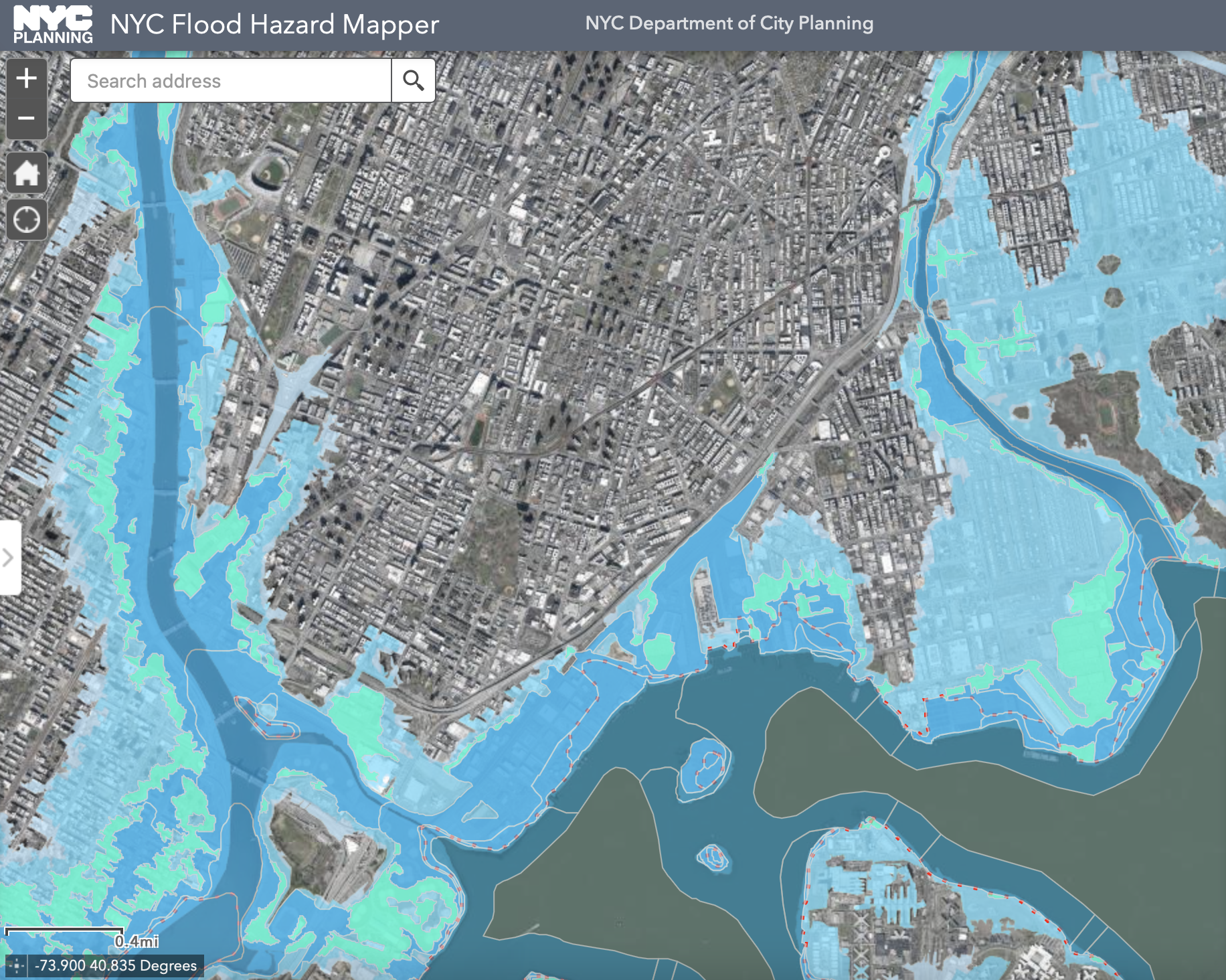

In 2011, the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance found that six of the seven SMIAs, including the South Bronx, are also in storm surge zones, making them especially prone to flooding.

This pollution will continue to become another hazard to the South Bronx’s health unless the city mitigates the effects of climate change. Addressing flooding and the health of local waterways is just one of the ways environmental justice organizations are working to make the Bronx more climate resilient.

“To some extent, we are locked into a set of risks that we’re already seeing. We’re seeing increased frequency and intensity of rainfall. We’re seeing sea levels are rising, more frequent and intense storms,” said Tyler Taba, senior manager for climate policy at Waterfront Alliance.

“How can we redirect that water? Or slow down the process of that water going into the sewer system during a heavy rain event?” he continued. “That’s a two-pronged solution, because you’re addressing the flooding, but you’re also addressing the water quality issue.”

Solutions for flooding generally fall into one of two camps: gray or green infrastructure. Gray infrastructure solutions include expanding the sewer system, underground retention tanks, building wastewater treatment plants, and other ways to control the flow of water. Green infrastructure uses nature-based solutions to absorb the water before it can flood streets or enter the sewer system, like rain gardens, green rooftops, and bioswales.

“We know that gray infrastructure is obviously necessary, right? There’s some things that you just can’t solve with trees and grass and flowers,” said Murphy. “But where there’s opportunity for us to renaturalize things and get more of that natural greenery and let the earth do the thing that it does best, we’re going to pursue that as much as we can.”

Green infrastructure also has the co-benefits of restoring wildlife, fighting air pollution, reducing high temperatures caused by the urban heat island effect, and creating more natural spaces for the public.

“These spaces offer a lot of healing for our communities, which have been through a lot over the past few decades,” said Matthew Shore, organizer of South Bronx Unite’s Green Space Equity & Community Land Trust. That organization created a Mott Haven-Port Morris Waterfront Plan with the aim to redesign portions of the South Bronx SMIA for public use.

“Studies have shown that waterfront access, waterfront proximity really provides benefits for people’s mental health, as well as their physical health,” said Shore.

The Waterfront Plan makes extensive use of green infrastructure to bring more natural settings to the South Bronx, which would also help to lower the chances of flooding that SMIAs are vulnerable to. The proposed Lincoln Avenue Waterfront, for example, would include a pier, multi-use trail, and a living shoreline, which uses native vegetation and other natural elements to stabilize a coast. Research shows they are more resilient to coastal storms than concrete bulkheads, a form of gray infrastructure.

Another gray infrastructure solution to coastal flooding proposed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has been met with some controversy locally. The federal study suggests building a variety of structures to prevent flooding, including tall concrete flood walls on the Port Morris Waterfront. While flood walls are effective flood protection, advocates say the plan does little to protect the area from flooding while continuing to cut off public access to the waterfront.

The current site of the proposed Lincoln Avenue Waterfront, a small section of public land between Lincoln Avenue and the Harlem River, has only a bulkhead crumbling into the water and a patch of empty grass.

“If these were green spaces, and if there were some particular ways that landscape was designed to allow people to sit and congregate in community, flooding events would be mitigated. And not only that, people would have a space to enjoy and feel good in,” said Shore.