At the very end of Lincoln Avenue, between the Willis and Third Avenue bridges, hidden behind trucks from the waste treatment plants and FreshDirect headquarters, 30 people gathered on September 7 for an end of the summer BBQ on the proposed Mott Haven-Port Morris Waterfront Plan. They were staking a claim. South Bronx Unite, the local environmental justice group that’s been working for years to transform this stretch of land known as Harlem River Yard, beside the skinny Harlem River into a park, a greenway, a place to breathe, had something to hope for.

At the end of the month, they will submit a grant application with the Bronx Economic Development Corporation, hoping it will bring them closer to the transformation they envision: a community-managed waterfront. If they win the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental and Climate Justice Community Change Grant, as much as $20 million could flow into the waterfront reclamation project.

If it happens, the Bronx Economic Development Corporation and South Bronx Unite’s fiscal arm, the Mott Haven/Port Morris Community Land Stewards, would be required to begin implementation of the first phase within six months of receiving the award, constructing the Lincoln Avenue Waterfront and the 132nd Street Pier with an estimated completion date of 2027.

“Being in the Bronx, you’re kind of boxed in with the highways and everything so it would be good to have access to some fresh air, with the water, and bring the kids around,” said Arion Cody, 35, who came to the BBQ after seeing South Bronx Unite’s flier on their Instagram.

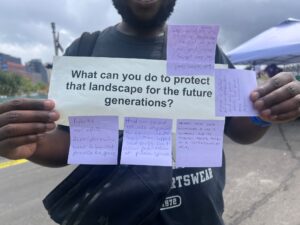

Many of the attendees brought their children, who played on the small grass strip that New York State subleased to the Galesi group for 99 years. Alongside the local vendors, members from the Korea Art Forum taught residents words in Nahuatl, Lenape, Spanish, and Taíno in an interactive linguistic bingo game.

Amidst the fun was a serious message: the fight for the South Bronx end of the Harlem River waterfront is ongoing. But the people are already making the place the thing they want it to be.

“We’re building residential housing, but we’re not building or increasing our infrastructure,” said South Bronx Unite co-founder Mychal Johnson. “So it’s a two part problem. One is how do we deal with sewer overflow? How do we deal with rainwater? How do we deal with climate change and sea level rise? And then the third is recreational opportunities for a community that has the least quantity of green space per capita than any other New York community… [But] we’re shouldering so much environmental burden.”

The plan the group is hoping the EPA will fund is an effort to address some of those long-standing inequities.

Receiving the grant would bring the Mott Haven-Port Morris Waterfront Plan into reality, after a decade of meetings in which groups of students, residents, and activists dreamed up what they wanted to see beside the river. The project will create accessible green space and protection from the storm surges and rising sea levels coming with climate change.

The campaign has strong support from elected officials, including Rep. Ritchie Torres. “I’ve sent letters of support for the project and advocated in its favor directly to Mayor Adams’ office. The Bronx has historically gotten the short end of the stick for federal investments, and I am determined to change that,” Rep. Torres said in a statement.

Mott Haven sustained up to four feet of flooding during Hurricane Sandy in 2012, damaging up to 61 properties with no flood-reduction protections. Children in the South Bronx have the highest asthma rates in New York City. Residents attribute health issues in part to the diesel-intensive operations of Fresh Direct and Waste Management that are housed on Harlem River Yards. The New York State Power Supply also operates a heavily polluting peaker plant, at the site, a backup energy transmission plant that is used during peak energy periods, such as hot summer days.

“This is also to hold [politicians] to account too,” said Mott Haven resident David Rosales, 25. “They talk about the impact of pollution and the toxic infrastructure that we see all around us. So this plan, of course, is us fighting, the community fighting forward against creating their own solutions.”

The plan has an estimated cost of $145 million. A holistic benefit-cost analysis by ecological economists at Earth Economics projected the construction would create $258 million in social, economic, and environmental benefits including temporary and permanent job creation, reduced health costs, and stormwater management.