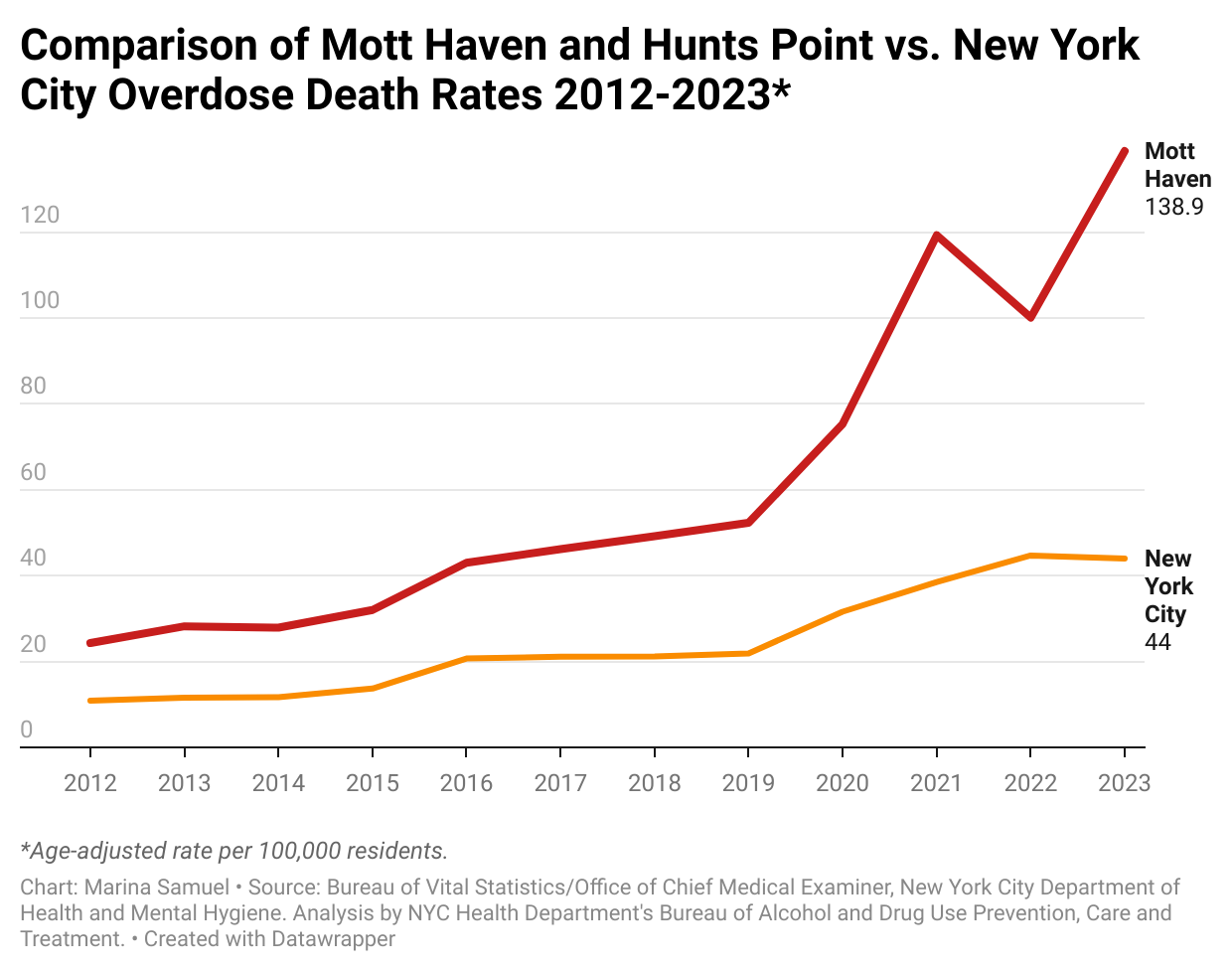

Nearly 800 people in the Bronx died in 2023 from opioid-related overdoses, the most in the five boroughs, according to data released by the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene last October. Community leaders and elected officials have been searching for ways to address the persistent opioid crisis in the South Bronx.

One proposed solution that has been shown to prevent overdose deaths calls for opening the borough’s first overdose prevention center in the South Bronx, which would give people an indoor space to use illicit substances under the supervision of a trained professional, who can recognize and reverse overdoses.

However, overdose prevention centers face political obstacles from the federal and state governments.

Cuts to federal funding under the Trump administration could potentially affect the harm reduction services that these centers provide such as case management, professional development, and mental health and wellness programs. Against the recommendations of her Opioid Advisory Board, Gov. Kathy Hochul refuses to tap into the state’s multi-billion dollar pharmaceutical settlement fund to finance these centers.

Bronx Borough President Vanessa Gibson had previously directed her efforts towards attaining settlement funds for less controversial initiatives, such as the new $6 million Bronx Recovery Center at Lincoln Hospital. For the first time, she proposed the possibility of an Bronx overdose prevention center at a City Council oversight hearing for opioid settlement spending in January.

“With the opioid settlement fund and the millions of dollars at our disposal, we want to make sure that the Bronx is protected, respected, we are valued, and included in this process,” Gibson said at the hearing.

OnPoint NYC currently operates two overdose prevention or safe injection sites in Manhattan, and expressed interest in bringing one to the South Bronx during a September meeting with Bronx Community Board 1 and local harm reduction advocates. Sam Rivera, executive director of OnPoint NYC said the Bronx would benefit from a center.

“The need is here, and the need is clear,” Rivera said.

Hochul said she won’t allocate money for overdose prevention centers because of federal statute 21 USC § 856 of the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, or the “crack house statute,” which prohibits opening or maintaining a site with the intention of “of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance.”

But advocates of overdose prevention centers argue that the federal law, which was passed during the War on Drugs era and is notorious for having disproportionately criminalized Black and Brown communities, is outdated and vague.

State funding for overdose prevention centers has become even more crucial as the Trump administration announced its plans to severely downsize the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) division of the Department of Health and Human Services. According to the New York Times, the agency could face significant reductions in grant funds, like State Opioid Grants, which support overdose prevention, treatment, and recovery services. While overdose prevention centers do not receive federal grants, reduced funding could strain existing service providers in the Bronx.

The OnPoint NYC sites in East Harlem and Washington Heights are the only two government-approved centers on the east coast. They were commissioned by then-Mayor de Blasio in the last weeks of his term in 2021, in an agreement with the NYPD and district attorneys. OnPoint NYC, which runs these sites, said there has not been a single overdose death under their supervision, and that they prevented 636 overdose deaths in their first year. But they operate in a legal gray zone and are at risk of being shut down.

The Opioid Advisory Council also called on Hochul to declare a public health emergency, granting her executive power to authorize overdose prevention centers and easily distribute funds despite the federal ban.

In a statement to the New York Times last August, the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York Damian Williams said that overdose prevention centers are “in violation of federal, state, and local law” and warned that his office may attempt to close the two existing sites.

The governor previously took a neutral stance toward the centers, but announced her opposition in 2023 after Dr. Chinazo Cunningham, commissioner of the Office of Addiction Services and Supports (OASAS), rejected the advisory council’s request for funding centers as it “violate[s] various State and Federal substance-related laws.”

Credit: Susan Watts/Office of Governor Kathy Hochul.)

While serving as lieutenant governor under Andrew Cuomo, Hochul sided with de Blasio and Adams to greenlight the pilot program, with Adams pledging to build an additional three centers by 2025, including one in the South Bronx. But as Hochul seeks reelection, and Adams faces federal indictment, neither appears eager to champion a politically contentious initiative.

“It’s not a question of whether they work,” said Toni Smith, New York State director of Drug Policy Alliance. “It is a question of how elected officials think it’s going to play among their constituencies. [W]hether we are able to authorize overdose prevention centers is not a matter of law. It’s a matter of political will.”

Without the governor’s support, the future of new safe injection sites is in the hands of state lawmakers. In 2017, the Safer Consumption Services Act was introduced in the state senate. The latest version of the bill advanced to the Senate finance committee during the last legislative session. State Sen. Gustavo Rivera, who introduced the bill, represents many Bronx neighborhoods with high overdose death rates.

The bill did not make it out of committee and onto the floor before the end of the 2024 legislative session.

“We heard that this is a politically charged bill and will not come to the floor for a vote in an election year because elected representatives don’t want to have to take a vote on a contentious bill or controversial bill in a year that people are going to be voting for them,” Smith said.

Sen. Rivera plans to reintroduce the bill in this year’s legislative session and continues to meet with neighborhood stakeholders to understand alternatives to criminalizing substance users, he said in an email.

“We need a comprehensive public health approach and I firmly believe that Overdose Prevention Centers (OPCs) are a part of the solution that could help us address this complex issue,” he said.

“This is not just about harm reduction; it’s about providing a real pathway to recovery for those struggling with addiction compassionately. I believe that prioritizing public health and safety is our moral obligation.”