By the time Justin Sanchez was seven years old, he learned how to administer albuterol to his three-year-old sister to treat her asthma. This wasn’t something out of the ordinary for him or his other Bronx neighbors. It seemed like everyone around him shared a commonality: asthma affected them or someone in their life.

“We’re always dealing with asthma, and it was kind of a daily norm of life,” says Sanchez, Director of External Affairs at the Office of the Bronx Borough President. “Then as I got older, I realized that one of the major contributors to our asthma and asthma related health issues was the Cross Bronx.”

So Sanchez started thinking of how to help the situation. His idea was to dig deeper into the concept of capping the Cross Bronx Expressway, covering the highway with open, green spaces. He turned it into a full-fledged proposal as part of his capstone project for the CUNY School of Urban and Labor Studies and now he’s working to make it into a reality.

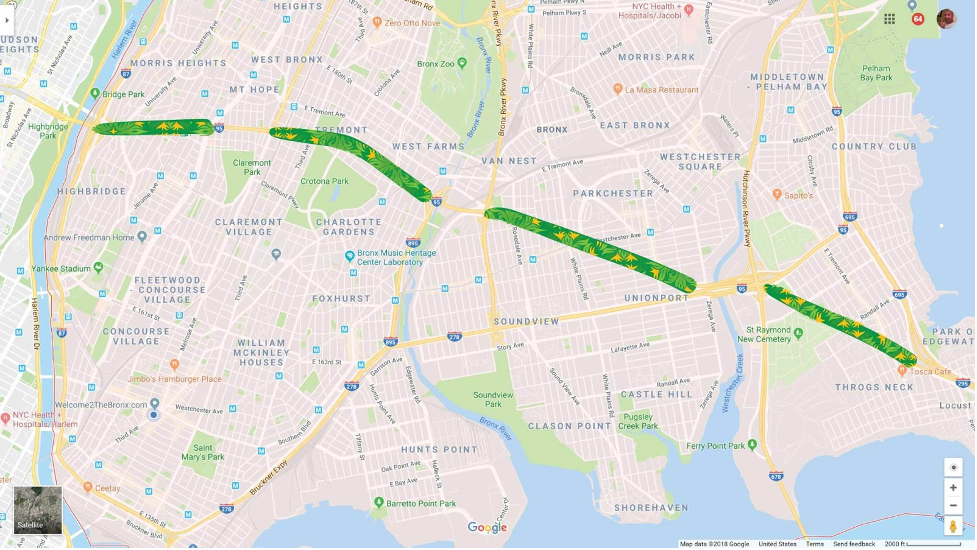

Robert Moses’ name is notoriously connected to many transportation projects in the tristate area, but none more infamous than the Cross Bronx Expressway. The 6.5-mile-long highway cuts straight through the borough en route to places like Connecticut or Long Island. Built in the mid 20th century, the idea was novel at the time, but early on, surrounding communities felt the immense impact of the expressway on their lives.

With three major highways passing through areas of the Bronx- the Cross Bronx, Major Deegan and Bruckner- cars and trucks leave behind toxic fumes creating unhealthy air quality and higher rates of chronic illnesses. According to a 2018 NYC community health profile, the air quality of Mott Haven, for example, was 8.6 micrograms, much higher than the citywide average of 7.5 micrograms. This can lead to chronic health conditions, like asthma, where the Bronx averages more than 23,000 asthma-related emergency room visits per year, almost 10,000 more than Manhattan.

“The major health issues in the Bronx are chronic disease: diabetes, obesity and high blood pressure” says Peter Muennig, Professor of Health Policy and Management at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University. “All of those things are related to air pollution, exercise and mental health.”

Working in preventative medicine, Muennig and other researchers published a report in 2018 detailing a proposal to cap sections of the Cross Bronx Expressway to turn into parks as a way to alleviate some causes of chronic health conditions. Similar to the goals of Sanchez’s proposal, the study found that the capping project would increase life expectancy for surrounding residents by roughly two months by decreasing pollution, increasing exercise and staving off pedestrian accidents. Air pollution extends beyond the bounds of the immediate neighboring areas of the highways, the entirety of the Bronx will feel the effects of improved air quality due to capping.

A little over two miles of the Cross Bronx are designated as “below-grade” meaning traffic runs underneath the street level. These parts of the highway would be easiest to cap as level development could happen on top. The other four miles have a solution, too. Raised decks on top of the road would create a tunnel for traffic. Pollution would be trapped inside the tunnels, filtered through a vent, accidents would be reduced and parks would serve as an alternative to congestion, under Muennig’s plan.

Unlike Muennig, Sanchez isn’t limiting his plan to the below-grade sections. He’s going for the whole thing.

“I believe that it is not a success until it’s all been capped” he says.

Sanchez is firm on his belief that Robert Moses left such a negative legacy on the Bronx and the borough’s residents deserve restitution for his impact.

“I believe the best way to do that is providing a full cap of the Cross Bronx and being able to mitigate issues all across the borough” he says.

Another Bronxite, Nilka Martell, has been focusing her efforts on a much smaller scale. A lifelong resident of the borough, Martell recently campaigned for the renovation and restoration of Virginia Park in Parkchester through her organization Loving the Bronx, which advocates around local environmental issues. That got her thinking about a small portion of the Cross Bronx that runs directly next to it.

“It’s this below-grade open portion of highway. It’s probably a little more than an acre. But there is no reason why it should be open” says Martell.

Along with fellow community members and activists, Martell recently approached city officials with the idea, citing the many health effects of playing and living so close to all those toxic fumes. But, she says, they weren’t taken seriously.

“They looked at us and were like ‘your idea is cute’ but you need someone who is really qualified in this,” says Martell.

That’s when Martell found Muennig’s report. It supported everything she was pushing for. Using the report and other tools, Martell has been trying to mobilize the community and beyond to garner support for the plan.

Martell’s goal is to focus on that one acre of highway, instead of Sanchez’s 6.5 miles and Muennig’s 2.5 mile plans. She thinks it will be a major win if that smaller area is capped and green space is extended because it will personify the bigger picture, giving a tangible example of what can be done to the whole stretch of the highway.

Martell imagines an amphitheater on top of the Parkchester capped portion, but recognizes that community input will be vital in these decisions on what is put above the tunnels. She’s heard calls for dog parks and housing as well.

The project is still in its early stages of action. There isn’t a clear cost estimate, with different hundred-million dollar figures being thrown around. Martell is hopeful that progressive politicians like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who represents a portion of Parkchester where the Cross Bronx cuts straight through, will be supportive of the plan, especially because it aligns with Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal.

Capping highways is not a foreign concept, in fact, it’s been done before. Cities like Seattle, Dallas, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Denver have all utilized highway capping to promote more effective use of city space, and create healthier communities. Other places like Atlanta and Minneapolis also have plans in the works to bury highways beneath parks.

Martell is hopeful that the Bronx will reclaim some of the real estate the Cross Bronx has taken up for too long. To do that, Martell says it will take a movement powered by locals.

“I just want people to go away knowing that people have power. Too often we feel like we don’t” says Martell. “If you live here and this is what you really care about, you don’t have to be the professional person with all the letters at the end of your name. You can just be that regular person and just really organize people to create that change.”