Some South Bronx community members and elected officials call for end to mayoral control, others argue to extend

Farah Despeignes, a former teacher at Samuel Gompers High School in Mott Haven for 14 years, doesn’t think New York City’s centralized education policies always do a good job serving the unique needs of the South Bronx, and wishes the community had more input into what is taught and in education policy overall.

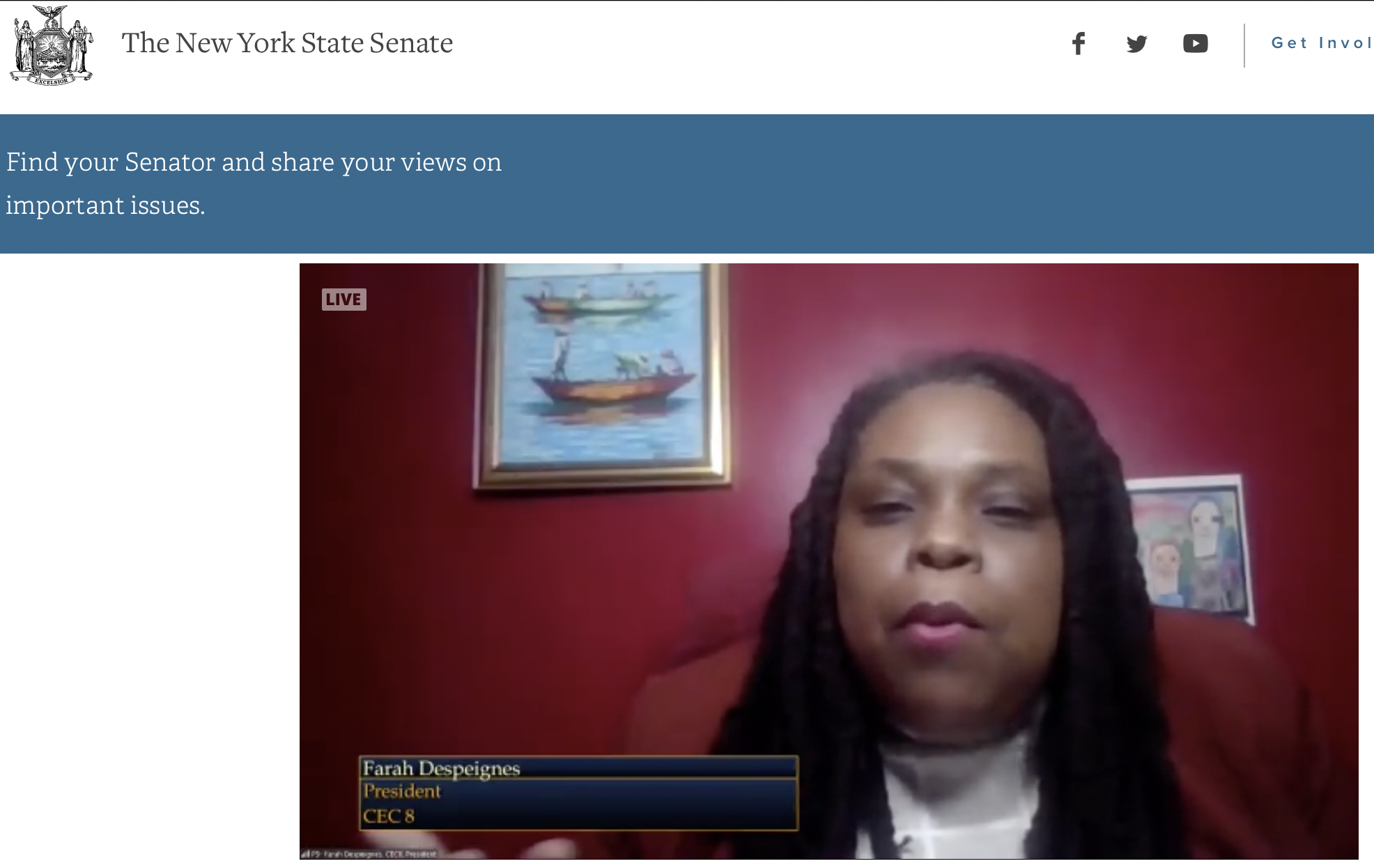

“In the Bronx, education has to look somewhat different than it looks in a place where everything is well,” Despeignes testified at a March 4 legislative hearing. “You cannot treat a poor child that doesn’t have heat in their home or doesn’t eat three times a day the same way you teach someone who goes to Europe every summer and has a house in the Hamptons.”

In the coming weeks, New York State lawmakers will decide whether parents and teachers who share her views are granted greater authority in decisionmaking over their local schools – or whether all city schools will remain under mayoral control.

For the past 20 years, the city’s Department of Education has been under mayoral control, which means the mayor has the power to appoint and fire the schools chancellor, and also appoint nine of the 15 members of NYC’s Panel for Educational Policy (PEP), which serves the chancellor in an advisory role.

Before 2002, city schools were governed by a citywide Board of Education plus 32 community boards that faced frequent charges of mismanagement and corruption. Former mayor Michael Bloomberg sought, and was granted control by the Legislature, which oversees education policy across the state. Bloomberg then closed a number of failing schools, opened several smaller schools and encouraged charter schools, but also made school data more transparent.

Most education systems are not run by their mayor. And in New York, mayoral control must be re-authorized every few years. It is set to expire on June 30.

Gov. Kathy Hochul included a four-year extension in her state budget proposal, which has an April 1 deadline for approval. But the Legislature decided to remove the extension from the budget to allow more time for deliberation. Lawmakers now have until June 30 to act.

The March 4 hearing lasted seven hours – an indication of the strong feelings surrounding mayoral control. Mayor Eric Adams spoke for the first five minutes and then left without taking questions or listening to other testimony. Others who weighed in were Schools Chancellor David Banks, Senate and Assembly members, and over 40 others, mostly parent advocates.

“A four-year extension of this transformational policy will allow me four years to do what I know needs to be done based on my time as a senator, as a law enforcement officer, as a senator, as a borough president,” Adams said shortly before leaving the meeting.

While Adams and Banks pitched their case in support of extending mayoral control as it stands for another four years, the majority of stakeholders said they were opposed. Some argued that there should be no extension at all. Others suggested a shorter extension, to give the Legislature time to create an alternative system and to ensure that the mayor can be held accountable before the end of his four-year term, which began in January.

Assembly member Amanda Septimo, whose district includes a big part of the South Bronx, said the current system of mayoral control “isn’t working” and that she’s willing to advocate for a new system that gives parents more power.

“I constantly hear parents not feeling involved enough –– decisions being made about schools without them,” Septimo said. “There are many times it seems that parents are treated as thoughtful opinion givers, but not necessarily viewed as equal decision-making partners. I think that leads to policies that disregard the role that parents should be allowed to play.”

Despeignes, who is now president of Soundview’s Community Education Council 8 and founder of the NYC Coalition for Educating Families Together, said that under mayoral control, decisions are made without input from educators, parents or students on the ground. Since the inequality gap in NYC is so high –– and communities have such different needs –– broad school policies made by the mayor and aimed to blanket the entire city sometimes neglect marginalized communities’ needs, she said.

For example, she noted, the “heavy lifting” to get kids prepared for learning is so much greater in low-income communities: “If you’re not on the ground and you’re not in people’s homes and you’re not sharing their experiences, how do you know [what they need]?”

State Sen. Luis Sepúlveda, who represents parts of the South Bronx including Longwood and Hunts Point, said at the hearing that he’s confident Adams will meet his district’s needs. Sepúlveda said he’s concerned about his district’s graduation rates and thinks mayoral control under Adams will help.

“[A two year extension of mayoral control] is insufficient to get results for the changes you [Banks] are trying to implement,” Sepúlveda said. “I am in favor of a four-year extension and will continue to advocate for four years so that you and the mayor have the time to establish what you want to establish with our kids.”

State senators Alessandra Biaggi and José M. Serrano, whose districts include Hunts Point and Mott Haven respectively, did not respond to questions about their thoughts on mayoral control, even though they eventually will vote on it.

Chancellor Banks said he recognizes there are flaws in the current system and that parents aren’t listened to enough. But Banks repeatedly reminded lawmakers that both he and Adams grew up in New York City and attended public schools. He said he is committed to “engaging” with parents at all times during policy creation and implementation.

“I do not want to create policy where families feel that they have not been part of the process,” Banks said. “That will not happen with me as chancellor. I just got here, but I am fully committed to this.”