Residents want Manhattan waste transfer station to lessen local burden

Mott Haven residents and activists told several mayoral candidates at a June 12 forum that whoever wins the election next November should make sure no additional trash is transported to the South Bronx for processing.

Some 300 attendees heard 10 candidates describe their policies at a June 12 public meeting at Hostos Community College, on issues ranging from education to immigration.

But the topic that drew the loudest public response was the city’s policy for treating waste, and what residents say is the disproportionate role the area plays in handling it.

Attendees inside and protesters outside the campus’ main building on the Grand Concourse told the candidates they want the city to proceed with a plan to open a marine transfer station on E. 91st St. on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, and reduce the local burden.

The candidates were split on the Upper East Side site.

“It bisects a development for children,” said Bill Thompson, the city’s former comptroller, explaining why plans calling for the E. 91st St. site to be opened should be scrapped.

“Hundreds of thousands of children use that site – many from East Harlem. It’s a bad site,” he said, drawing jeers and hisses from the audience.

“It’s a good site,” one audience member shouted back angrily.

The city’s 2006 Solid Waste Management plan calls for three marine transfer sites in Manhattan, including the one at 91st St. and York Avenue, which would handle about 30 percent of Manhattan’s residential waste.

“Manhattan is not handling any of its own waste,” said Angela Tovar, policy director at Hunts Point environmental group Sustainable South Bronx, adding that the South Bronx, North Brooklyn, and Southeast Queens handle 75% of the city’s waste. “We are voters, and we’re waiting and ready for a more equitable system.”

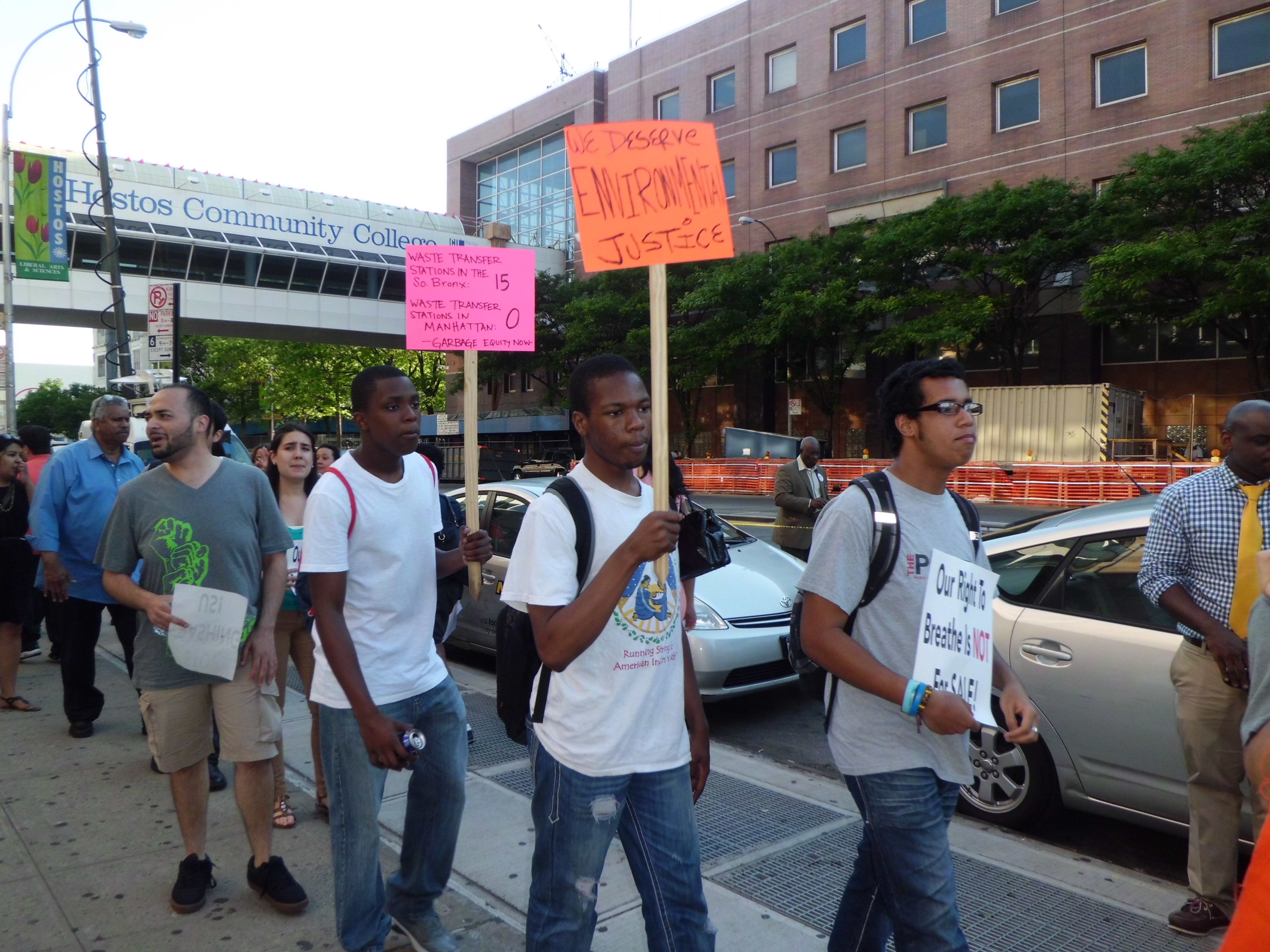

Protesters from Sustainable South Bronx, South Bronx Unite and other environmental justice groups, marched in a circle outside the building, chanting, “We need a mayor to make things fair, to clean up our polluted air.”

Hunts Point hosts 11 waste transfer stations. Port Morris is home to six more. Environmental advocates blame the area’s staggering asthma rates, which are eight times the national average, on the thousands of truck trips made every day to and from those plants.

“Why is it that the South Bronx is continually being used as a dumping ground?” asked Mychal Johnson, a co-founder of the grass roots group South Bronx Unite.

But former US Congressman turned-mayoral-candidate Anthony Weiner dismissed the notion that opening the 91st Street station would cut into the Bronx’s pollution problem.

“It does not go to the Bronx,” Weiner told the gathering. “Anyone who tells you otherwise is not being honest with you.”

Public advocate Bill de Blasio and City Council speaker Christine Quinn argued that the site is a crucial part of the city’s Waste Management plan, and should not be removed.

“You cannot take out one piece of the plan,” said de Blasio. “The site has to stay there. We can help to mitigate the effect, but you cannot remove that site.”

If the site is not opened, Quinn said, garbage would continue to be transported through Harlem, as it is now, down Manhattan’s west side, and into New Jersey.

“Is that fair for Harlem, a neighborhood with higher asthma rates than the Upper East Side?” she said, noting that she supported building a transfer station in the West Village, which she represents in the council. “I wasn’t going to put something in somebody else’s district that I wasn’t willing to put in mine.”

Candidates also debated immigration reform, arguing the merits of a municipal ID for undocumented immigrants. Brooklyn pastor Erick Salgado called for a city identification card for immigrants, but City Comptroller John Liu questioned the usefulness of the card, arguing that immigrants should have the same ID documents as citizens.

Salgado said young people suffer the most from the lack of documentation.

“When they go to school, they have to bow their head because they have none,” Salgado passionately declared, drawing loud cheers.

The candidates also considered ways to improve health care. Democratic candidate Sal Albanese said that if elected he would open pediatric centers that would focus on early childhood health and education in low-income neighborhoods, including Mott Haven.

“We don’t have an IQ issue, we have a poverty issue,” the former public schoolteacher from Brooklyn said, pointing out that “kids are coming to our school system way behind.”

For some attendees, the protesters who urged the candidates to reduce the South Bronx’s share of the city’s waste stole the show.

“Everyone has the right to clean air,” said Rosemary Jenkins, a social worker from Melrose, who stood in the ticket line next to the protesters before the event. “So we need someone who supports that project.”