Principal, pastor have a month to devise a plan

After 140 years providing an education for South Bronx children, St. Jerome Catholic School is on the chopping block.

The Archidocese of New York says it can no longer afford to keep the school on Alexander Avenue open unless the principal and the pastor of St. Jerome Church next door radically restructure the school’s plan to show it can pay a bigger share of its upkeep by increasing enrollment and raising tuition.

But the parents of some students and the school’s principal argue the proposed closing is part of a troubling pattern showing the Archiocese is no longer committed to providing a Catholic education for children in low-income neighborhoods.

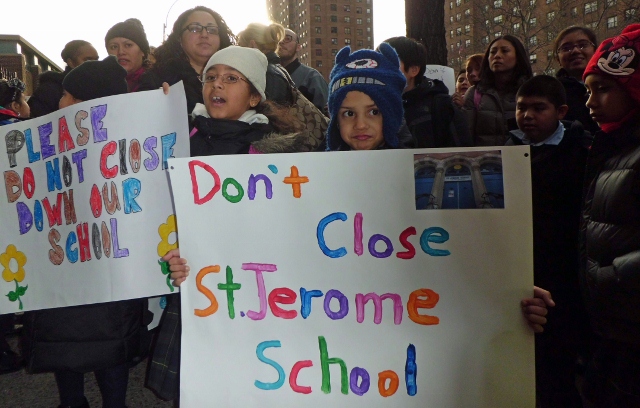

Some 50 parents and children rallied in front of St. Jerome on Dec. 12, urging the Archdiocese to reconsider plans it announced in November to shutter the school by Jan. 3 unless the pastor and the principal can show a “realistic” plan to raise $1.3 million within three years. There are just under 300 students in the school, which serves grades pre-k through eight.

Parents and school administrators say they were blindsided when the Archdiocese informed them of the news around Thanksgiving.

“Why did they wait so long to show we were in this difficulty?” said Michelle Feliciano, 45, whose six-year-old daughter has attended the school since she was three, adding, “No other schools in this neighborhood are worthy of my daughter’s education.”

Feliciano, who lives around the corner from the school and works for the MTA, said she pays $315 per month for tuition, along with a $350 registration fee, $150 for supplies and $125 per month for an after school program. In addition, she says she and other parents are required to raise $400 a year selling candy—or pay that amount out of pocket if they don’t.

“They should have let us know in advance,” said Nashaera Santiago, 38, a Mott Haven resident and postal worker with a six- and a three-year-old in the school.

“My goodness, talk about the fiscal cliff. We have our own fiscal cliff, but it’s dealing with our children,” the school’s principal, Joseph Puglia, told the crowd. “We are trying very hard to come up with a plan that is reasonable.”

But a spokeswoman for the Archdiocese said the policy of closing some schools is an unavoidable consequence of the protracted economic downturn, and has been regularly invoked since it was put in place three years ago. Charitable donations for various causes have plummeted as the economy continues to sputter, said Francine Davies, assistant superintendent of schools for the Archdiocese, and “hard evaluations and sad decisions have to be made,” to ensure schools earn enough revenue to keep them sustainable.

If St. Jerome is forced to close, Davies added, students and their caretakers will meet with counselors from the Archdiocese to devise a plan, and many will be transferred to “underutilized” Catholic schools in the city.

“We don’t want to lose a single child,” Davies said, but added, “You have to be smart and responsible.”

The Archdiocese formed regional boards to make decisions about the fate of its schools in 2009, a process Davies said enables residents and local clergy to conclude the best use of resources in their neighborhoods. But Kelvin Ramirez, 33, whose five-year-old son is in the preschool program, said the regional oversight boards are a good idea badly implemented.

“What they have to understand is this is an impoverished community,” he said, adding that the board deciding on St. Jerome’s fate serves too wide an area and “has no idea about this school.”

State Senator Jose Serrano told the throng that he had sent a letter urging the Archdiocese to give the school more than just a month to come up with a sustainability plan. Serrano added that he received his first communion at St. Jerome when he was five.

Clementine Burgos, 62, of Port Morris, pulled a yellowed 1984 edition of a local newspaper out of her handbag and pointed to an article in which she was quoted while rallying for new art and music programs at St. Jerome when her daughter attended. Those programs and a new gym were introduced as a result of parents speaking out, she said. Twenty-eight years later, Burgos was rallying on behalf of her granddaughter.

“Thanks to our voices, the school has risen to new heights,” she said. “It’s very important for this neighborhood.”