A revived NYPD anti-gun unit hit the streets of the South Bronx on Monday to combat a recent rise in crime borough-wide.

This is the first specialized anti-crime unit created since 2020, when they were disbanded by Mayor Bill De Blasio and Commissioner Dermot Shea as protests against police violence across the city and country put a spotlight on abuse and rampant profiling within the units.

Today, newly organized units are headed into neighborhoods to try and address rising gun violence as part of a new initiative announced in January by Mayor Eric Adams.

The new Neighborhood Safety Units are patrolling select Bronx neighborhoods, covering all of Mott Haven and Hunts Point, according to a map shared by the NYPD on Wednesday. The units were assigned to the 40th and 41st precincts in Mott Haven and Hunts Point along with 23 other precincts across the city that reported the highest rates of gun violence in 2021.

Rather than importing officers from other boroughs or hiring new officers, existing 40th Precinct officers have been training in preparation for these roles throughout February, 40th Precinct Commanding Officer Inspector Robert Gallitelli said.

Gallitelli explained how the precinct was preparing for the rollout at a community council meeting last month.

“They’re not really plainclothes because there’ll be police [written] across their chest,” Gallitelli said following announcement of the rollout. “They’ll be identified.” He explained that, like other units in the department that target the most violent crimes, the team will patrol in unmarked but recognizable cop cars like the ubiquitous black Ford Focuses used throughout the city.

This time around, the units wear a modified NYPD uniform and each officer wears a bodycam that must be actively recording during any interaction with a civilian.

These teams, announced by Adams as anti-gun units in January, have a controversial history marked by accusations and various findings of police brutality and abuse going back decades. Adams spoke out against abuses within the city’s Street Crime Units (another name for units of this style during the 1990s and early 2000s) during his time with 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care when he was an NYPD lieutenant in the 1990s.

Adams coordinated accusations of, and investigations of, racism within the unit, particularly following the murder of Amadou Diallo — advocacy that led to retaliatory undercover NYPD investigations against Adams and his team.

With that history, Adams and NYPD leaders are adamant that these new Neighborhood Safety Units will not repeat the mistakes of their predecessors, calling the former anti-crime units abusive and promising the city has done its homework vetting, outfitting and training officers in preparation for this deployment.

Gallitelli distanced the new units being deployed in Mott Haven, Port Morris, and Melrose from the anti-crime units of the past: “Anti-crime as we know it doesn’t exist anymore — it will never be the same.”

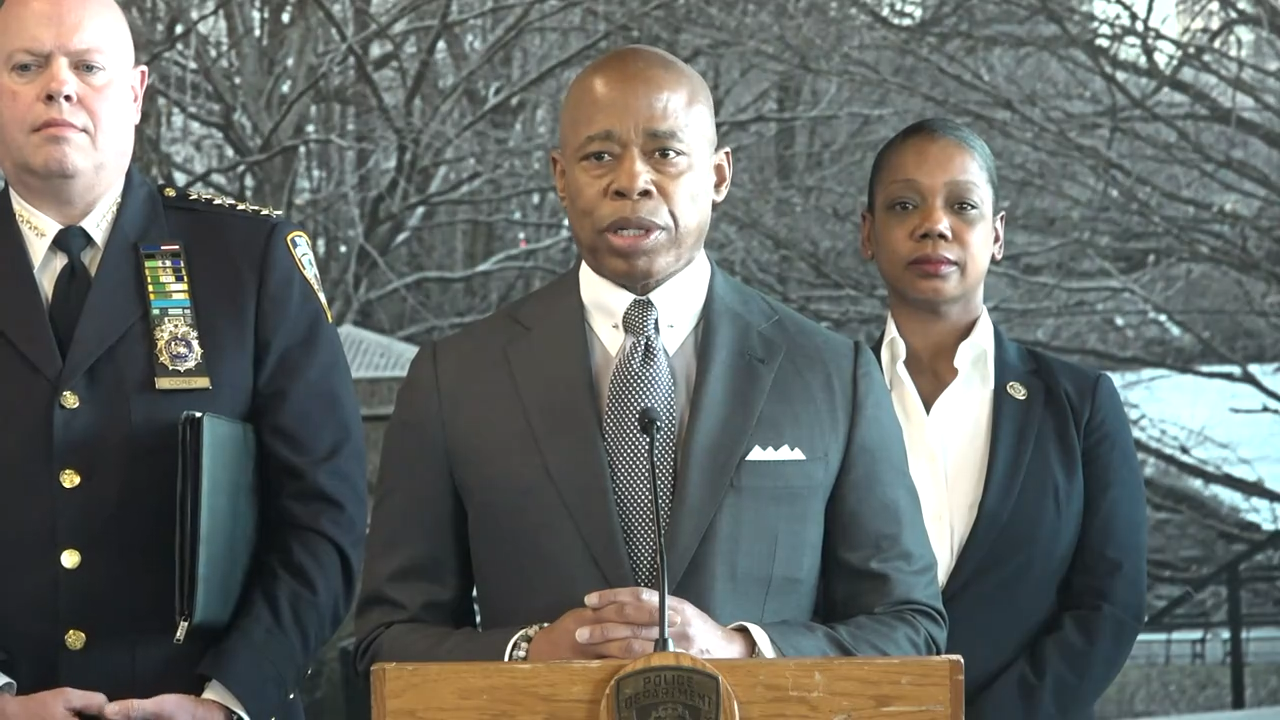

During a press conference at the NYPD academy in College Point on Wednesday, NYPD Chief of Department Kenneth Corey said that officer selection for the special teams was competitive and cautious. Corey said that officer body cam footage was reviewed to see how volunteers for the positions interacted with civilians, and judged their temperament for the new teams, a process that accompanied a vetting process facilitated by the NYPD Risk Management Bureau.

“I was not going to put out a unit that was going to go after those who are carrying illegal guns unless I felt comfortable that we were not going back to the days of being abusive,” Adams told reporters.

Following the announcement and in response to a question about civilian interactions with police and safe recording, the mayor complained about civilians crowding on-duty NYPD officers while documenting police activity.

“Stop being on top of my police officers while they’re carrying out their jobs. That is not acceptable and it won’t be tolerated,” Adams said. The mayor claimed that across the city there are incidents of civilians standing too close to officers, shouting “police brutality” at them, calling officers names, and creating a “dangerous environment.”

“You can safely document an incident and we can use that footage to analyze what happened, but that’s not what’s happening right now in our city,” Adams said. “We’re finding people who are standing on top of the officer while he’s involved in a dangerous encounter. [That is] not acceptable, and it’s not going to continue to happen.”

In 2020, the New York City Council passed legislation that formalized the rights of civilians to record police activity. The Right to Record Act also established a pathway in state court for individuals to sue the city if their rights are violated. The law does specify that this right does not cover “actions that physically interfere with law enforcement activity,” but there are no formal guidelines for New Yorkers on what constitutes a legal safe distance for protected police recording.