How would you spend $5 million?

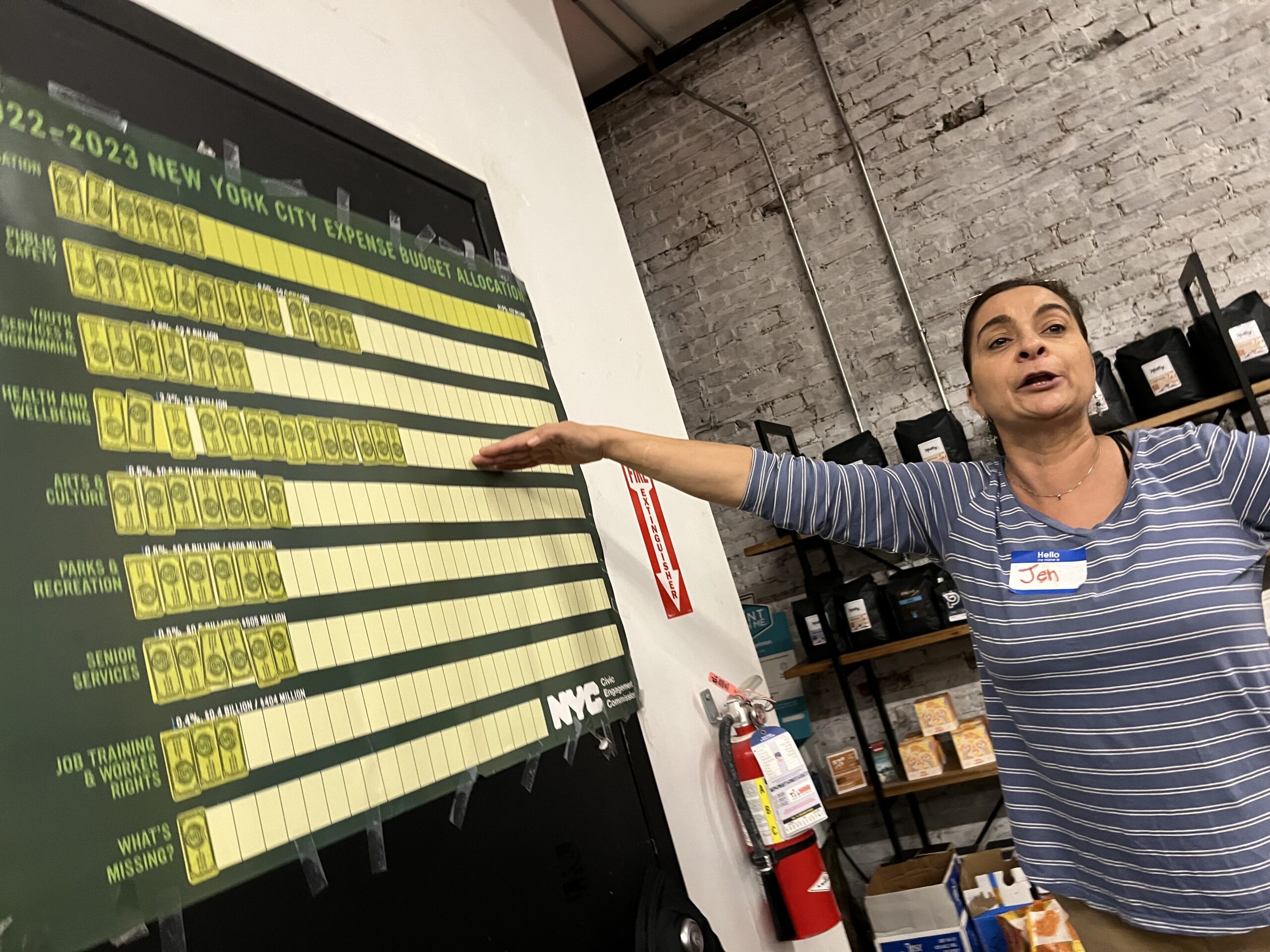

That’s the question dozens of Mott Haven residents asked each other at Mottley Kitchen on E. 140th street where they discussed programs that can improve health and public safety, which ranked as top priorities in their communities.

The meeting was one of many idea-generating sessions for the People’s Money, a participatory budgeting process run by the Civic Engagement Commission. Over the next nine months, New Yorkers will meet to propose, evaluate, and vote on programs to improve their local communities. Successful proposals will receive government funding.

This process allows communities to identify problems and solve them in ways that might not be obvious to professional politicians in the city government, according to Mott Haven resident Jennifer Yadav, who led the session.

“Eric Adams doesn’t hang out in our neighborhood,” Yadav said in a telephone interview, explaining why local people might have insights into these issues. “The people who are actually living here, who understand the issues in the neighborhood, it makes sense that those people come up with the ideas to spend some of that money.”

The People’s Money is open to everyone. Any New York City resident over age 11 will be able to vote on proposals, regardless of their immigration status, or past criminal history.

“These are programs that are going to be for everyone in the community,” Yadav added. “Regardless of whether someone is incarcerated or not, or is a citizen or not, these programs will be for everyone who lives here.”

Yadav is the secretary of the Mott Haven Blocks Association, a loose group of neighbors that come together to solve sanitation, noise and other quality of life problems in their neighborhood. The Blocks Association was one of 84 community groups that successfully applied to run idea-generating sessions.

Yadav says that they received a grant of $1,000 to run two sessions, which they spent on food, drinks, and prizes for those who attended.

This is not New York’s first foray into community-led funding, but it is the first citywide initiative and, at $5 million, the largest. Participatory budgeting initiatives have also been launched in Chicago, Boston, and Cambridge, Massachussetts.

However, there are some limitations. The People’s Money can only be used for expense spending, like training programs or workshops. Capital projects requiring new construction or renovation are excluded. Moreover, the $5 million allocation is barely a drop in the city’s $100 billion bucket.

Participatory budgeting originated in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and has since spread to over 7,000 cities worldwide, according to the Brooklyn-based Participatory Budgeting Project. The idea was brought to NYC by four City Council members in 2011.

There are now 30 Council members who allocate capital funds with public participation. Last year, the Commission on Civic Engagement allocated $100,000 through a participatory process specifically aimed at those between ages 9 to 24. Young voters chose five projects to fund, including an online mentoring space for young girls and a recycling program, both in the Bronx.

“Communities know what their problems are, and they know how to fix them,” said Elizabeth Crews, director of Democracy Beyond Elections, a campaign by the Participatory Budgeting Project that advocates for more community-led decision-making.

“It also changes the way we do democracy,” Crews said. “It’s not just about showing up every two years or four years, it’s also about coming together to listen to the needs of your community and learn.“

While the Participatory Budgeting Project is excited about New York’s first citywide process, the People’s Money is still much smaller than the programs in cities like Seattle or Paris. “We’re hoping that next year we see a much bigger allocation,” Crews added.

Last year, the city allocated $1.3 million through a participatory budget process to communities that were hardest-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. In Mott Haven and Melrose, a proposal for in-school programs received $40,000.

For this year’s initiative, the People’s Money already has 787 proposals listed on the website of the Civic Engagement Commission, 220 of which originated in the Bronx. One of them calls for a “Drama/Theater Program” to allow Bronx students to showcase their artistic talents. Another called for daycare assistance to help recent immigrants or people with low income.

By the end of the session at the Mottley Kitchen, Yadav said she had 16 new proposals. These ideas ranged from cooking and nutrition classes to programs that would help non-English speakers navigate the medical system.

All proposals submitted to the commission will be vetted and formalized over the next six months, before going to a public vote next summer, according to the Commission.

Some had reservations. “I like the idea,” said Bomani Kernizan, adding that it is “a bit restricted. I would like this to be a much more advertised thing, with a much more developed infrastructure.”

Others welcomed the chance for a greater voice in city spending. “Finally, something democratic,” said Marie Saint-Loth, a former hospital worker who now works in a mental health clinic.

The idea-generation process for the People’s Money will end on Nov. 9. You can find virtual and in-person idea-generating sessions here. And here’s a list of ideas generated to date citywide through the participatory budgeting project.